Students in my Biology of Addiction class tell me that the main reason they were interested in enrolling in the class was because of the alcohol lab:

The alcohol lab was designed to determine whether the ingestion of alcohol resulting in a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) less than the legal limit would still result in measurable, deleterious changes in balance and reflexes.

The procedure involved acquiring informed consent from students of legal age, who would do the following:

- Perform certain tests to measure their auditory reflexes, visual reflexes, and balance;

- Rapidly ingest (i.e., chug) weight- and sex-adjusted amounts of alcohol so that their BAC would rise to no more than 0.06%, which is below the legal limit in Tennessee, where my university, Christian Brothers University, is located;

- Wait an hour for the alcohol to be absorbed into the bloodstream and reach the brain;

- Repeat the tests which measured the aforementioned parameters and compare the results pre- and post-ingestion.

The beverage of choice for all students of all volunteers was a screwdriver, i.e. a mixture of orange juice and vodka.

Now I have a question for the reader:

Q: How many times have students of legal age gone to a bar to drink?

A: Innumerable times, yes? It’s part of emerging adulthood, yes?

Now try to imagine these students of legal age drinking a sufficient amount of alcohol to ramp up their BAC to 0.06% while being followed by their younger colleagues who are bearing clipboards. This was the scene over a 3-hour period of time, and the volunteer students admitted that it was a bit surreal to get a nice little buzz…while being followed by someone with a clipboard.

The volunteers performed 3 tests:

- Each volunteer stood on one foot for a maximum of 30 seconds, first with eyes open and then with eyes closed. While the students were standing on one foot, the other students (investigators) counted the number of “dance steps” that volunteers had to do in order to maintain their balance on one foot. This test was inspired by an experiment done by the students in the junior-level physiology class, in which they had to do the same task, where the intent was to show how important vision is to sighted people to maintain balance. In their case, no ingestion of alcohol was involved;

- Respond to an auditory stimulus, provided by an auditory/visual stimulus machine. The auditory stimulus was a beep, which initiated a timer. The timer stopped when the volunteer pressed a pad on the reaction timer shown below;

- Respond to a visual stimulus, consisting of a small red light, provided by the same auditory/visual stimulus machine mentioned in #2. The timer stopped when the volunteer pressed a pad on the reaction timer shown below.

This is a picture of the auditory/visual stimulus machine used in experiments 2 and 3.

Results

Given the low number of volunteers (n=4) in the experiment, the results were not statistically significantly different. However, they are suggestive:

- Dance steps with eyes open and closed: As expected, volunteers had to engage in more “dance steps” to maintain balance when they closed their eyes, and their performance was even worse after the ingestion of alcohol. Some volunteers could not stand on one foot for the full 30 seconds after ingestion of alcohol:

2. Response time following auditory stimulus: Volunteers showed a delay in response to an auditory stimulus:

3. Response time following visual stimulus: Volunteers showed a delay in response to a visual stimulus as well:

And here is where I asked the students to take a close look at the difference in response time to the visual stimulus test. It’s only 0.043 second, which doesn’t seem like much, but that span of time can make the difference between stopping in time or crashing a car.

At the time the students conducted this experiment, we in Memphis were informed that the daughter of a prominent meteorologist had died in a car crash the day before her younger sister was going to get married.

The family was going to have dinner at home, and they needed some last-minute groceries. The elder daughter, married, pregnant and accompanied by her infant daughter, offered to purchase the supplies, and she never returned. Her car was hit by a drunk driver, and she died immediately. There were no skid tracks on the road, and police estimated that the drunk driver was driving at a speed of 120 mph. The wrecked car of the deceased daughter was mounted on a truck that toured nationwide as a display of what could happen when drivers take the road intoxicated.

A decade later, police and civilians were still finding fragments of metal on the hill near the intersection where the collision occurred.

What makes this story even sadder is that the drunk driver was hurrying to the Shelby County Penal Center for his mandatory weekend stay…and he got paroled: Drunk driver who killed pregnant woman and infant child granted parole (actionnews5.com)

So I posed the following question to the students: Assume you are driving 120 mph. How far will you be traveling in 0.043 second? The answer is about 6.85 feet. Clearly therefore, very short periods of time can become highly significant when driving at high speeds.

None of this should be surprising, and although the results that I present were not statistically significant, there are studies that support the assertion that ingestion of sufficient alcohol to remain below the legal limit will still result in impairment.

In a review article, Martin et. al. (2013) quote Moskowitz and Robinson (1987): “…from a scientific point of view, there appears no lower BAC below which impairment cannot be said to exist. The legislature is free to prohibit driving at any BAC, since such a limit would not contradict the scientific data demonstrating no lower alcohol limit impairment.”

Martin et. al. (2013) also report the following findings:

- Impairment of the ability to divide attention and complex reaction time (i.e., choice reaction time) has been demonstrated consistently at BACs lower than 0.050%;

- A BAC of ~0.030%, cognitive functions, especially those relying on perception and processing of visual information, are significantly impaired;

- In a study of perception and reaction to a hazard, subjects took longer to detect a hazard, and when they did react, they reacted more abruptly at BACs ranging from 0.040% to 0.060%.;

- BACs between 0.025% and 0.075% produced a detectable increase in traffic hazard latency in a double-blind placebo-controlled simulator study;

- In a closed-course experiment, significant increases in number of pylons hit and stopping distance was observed, including for 10 subjects with BACs ranging from 0.024% to 0.042%.

So there is no threshold for harmful effects.

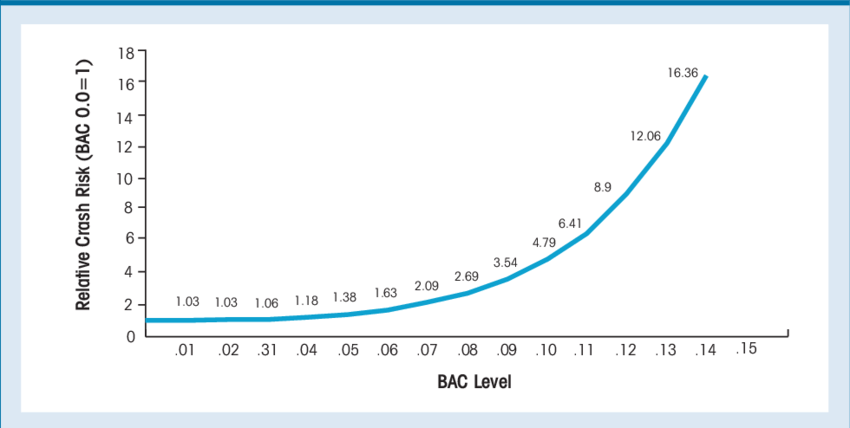

The following chart shows the composite relative crash risk as a function of BAC level. We can see that even at very low BAC levels, relative risk will rise.

When, however, relative crash risk is parsed out to consider age and sex among teen drivers, the results among males are more striking:

Males between the ages of 16-20, who already have a greater tendency to take risks, have a faster rise in relative risk than any other age group.

Martin, T.L.; Solbeck, P.A.M.; Mayers, D.J.; Langille, R.M.; Buczek, Y.; Pelletier, M.R. (2013). A Review of alcohol a impaired Driving: The Role of Blood Alcohol Concentration and Complexity of the Driving Task. Journal of Forensic Sciences, September 2013, 58(5):1238-1247. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.12227.

Moskowitz, H.; Robinson, C. (1987). Driving I related skills impairment at low blood alcohol levels. In: Noordzij, P.C.; Roszbach, R. editors. Alcohol, drugs, and traffic safety. T86. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Alcohol, Dugs, and Traffic Safety, 1986. Sept. 9-12; Amsterdam, Netherlands. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier Science, 1987;79-87.