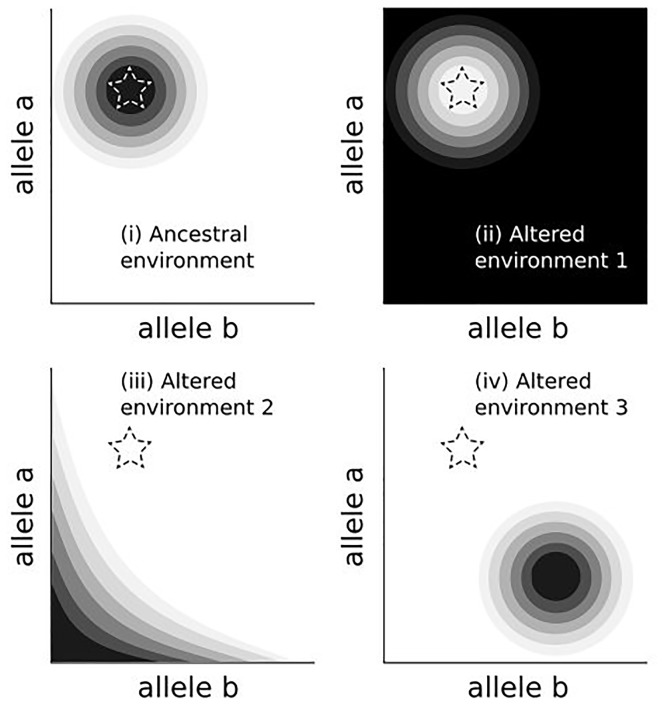

Melissa Manus (2018) defines evolutionary mismatch as “the phenomenon by which previously adaptive alleles are no longer favoured in a new environment (Fig. 1). This definition operates across space and time, while other uses of mismatch are applied over the life course.”

Figure 1: The ancestral environment (i) favours a certain combination of alleles (darker colours). Transitions to modernity produce shifts in the allelic combination that is best suited to the new environment (ii-iv). Mismatch occurs when ancestral alleles (star) persist in new settings where the environment, but not yet genetics, has changed.

The modern-day practice of gambling is one in which an individual wagers a certain amount for financial gain. However, this modern-day form of entertainment is very much related to risk-taking, which at one time, would make the difference between life and death.

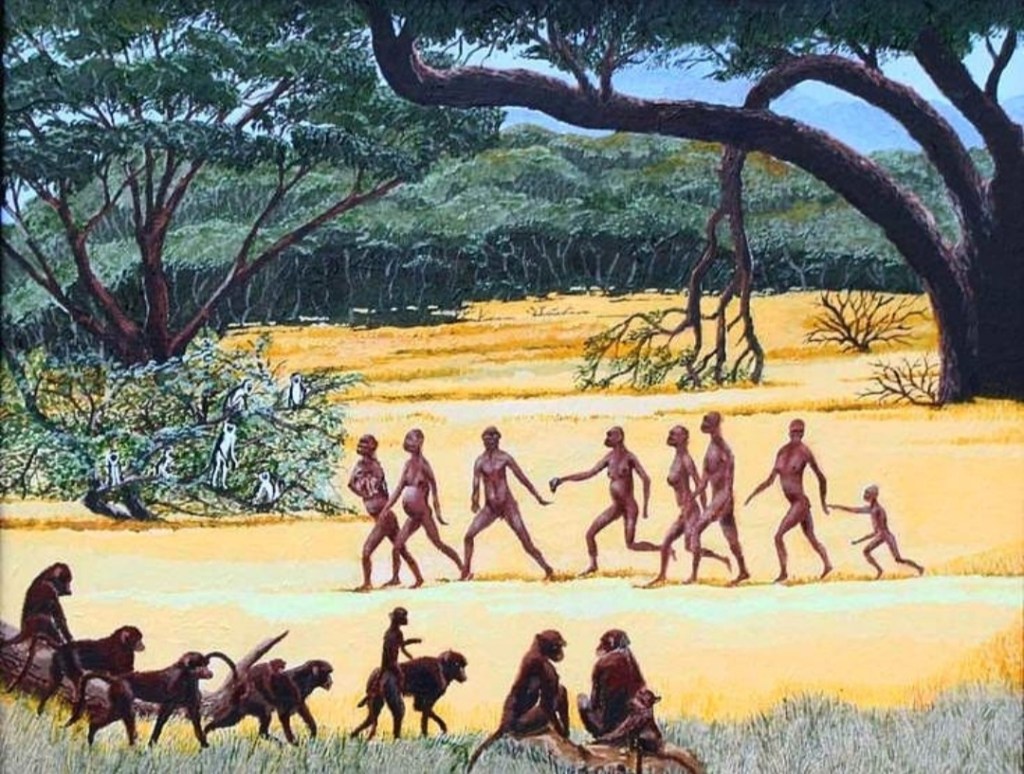

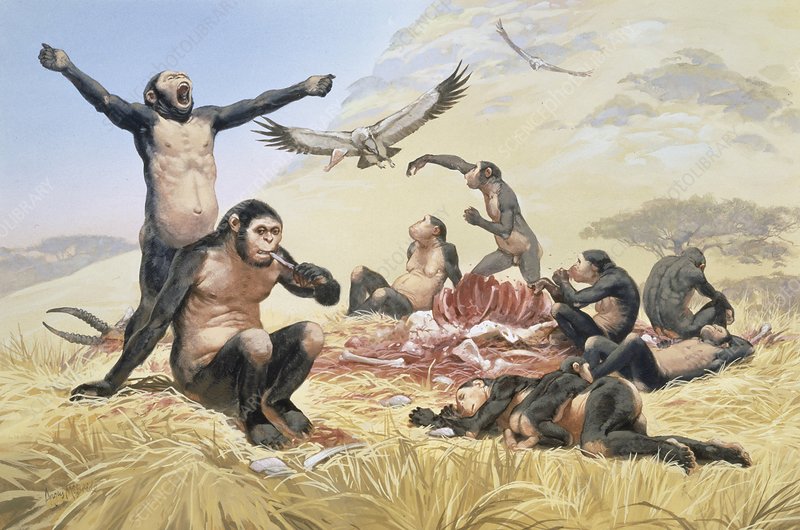

To make the point, I want the reader to imagine that you are now going back in time to visit a group of deep ancestors, and I don’t mean our grandparents or our great-grandparents, but rather a troop of Homo habilis, a hominid species who lived 2.8 to 1.65 million years ago in East and South Africa. Here are 3 views of our troop.

L-R. 1) Homo habilis family troop migrating across savannah; 2) Relatively equal size of females and males suggests that Homo habilis was the first to engage in monogamy; 3) Family troop sharing a kill.

According to Wikipedia’s description of the diet of Homo habilis, they “derived meat from scavenging rather than hunting, acting as a confrontational scavenger and stealing kills from smaller predators such as jackals or cheetas.” While cheetas are solitary hunters, jackals often hunt in packs to make it possible for them to bring down large prey. However, black-backed jackals have also been found to hunt alone or in mated pairs. Either way, it would take considerable cooperative effort to scare away a cheetah, with its formidable teeth and claws, or a pack of jackals, to steal the kill.

I would like to take a closer look at the figure on the right, which shows a male striking a triumphant pose, in my mind denoting a sense of accomplishment, as if to proclaim “Yay, our risk-taking paid off! We get to eat!” Or maybe he’s just yawning after a sumptuous meal.

In addition to eating meat, the diet of H. habilis was “flexible and versatile and that they were capable of eating a broad range of foods, including some tougher foods like leaves, woody plants, and some animal tissues, but that they did not routinely consume or specialize in eating hard foods like brittle nuts or seeds, dried meat, or very hard tubers.” ( https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/species/homo-habilis#:~:text=habilis%20was%20flexible%20and%20versatile,meat%2C%20or%20very%20hard%20tubers.)

As (scavenger) hunter-gatherers, Homo habilis had to constantly be on the move to find food. If the particular habitat in which they were living started to dry up, then they had to decide on whether to risk staying put, hoping for rain, or to migrate to another habitat where there might be abundant food.

There was great danger in being a member of a Homo habilis tribe. These hominids, like others, were likely prey to the hunting hyena Chasmaporthetes nitidula, and the saber-toothed cats Dinofelis and Megantereon. The Wikipedia account of Homo habilis describes evidence of the left foot of a particular specimen (OH 8) being bitten off by a crocodile, and the leg of OH 35, which either belonged to P. boisei or H. habilis, shows evidence of leopard predation. Both of these predators would pose considerable risk at or near a body of water.

In the time of Homo habilis, therefore, risk-taking was a constant endeavor, and the stakes were high:

- To chase away a primary predator to steal its food

- To avoid being the prey to a larger prey

- To find food when the immediate area hasn’t had sufficient rain.

But the rewards were also high:

- The individual, family unit, or tribe was able to survive another day with food;

- The hunt became the basis of story-telling which would result in bonding within and among family groups

These rewards are conspicuous in their absence in modern-day life. When a boss gives an employee a task to complete, and the employee completes the task, does the employee get a sense of triumph and empowerment? I would venture not.

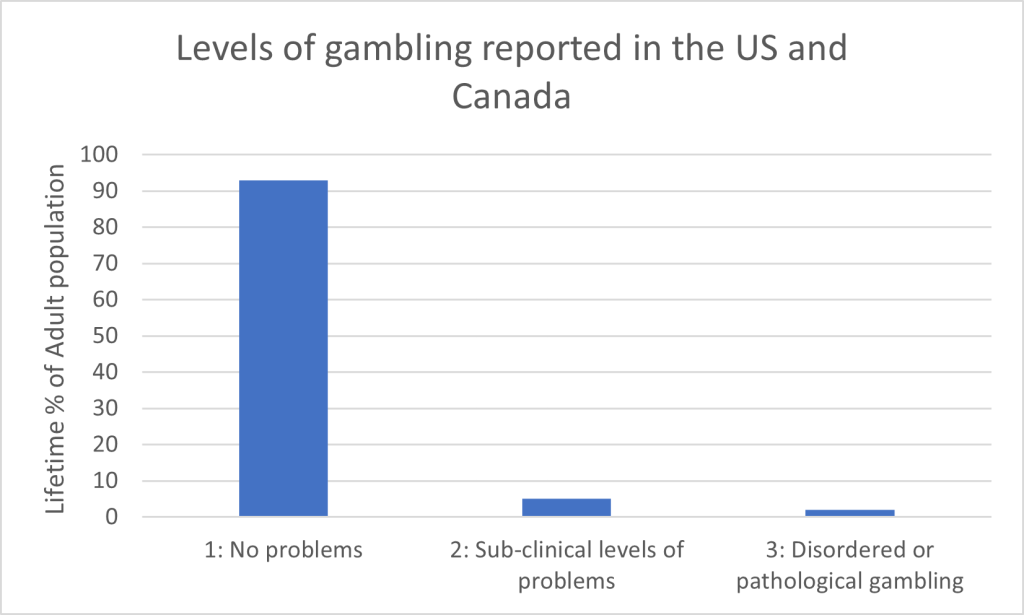

How prevalent is the problem of pathological gambling? Less than 10% of the adult population in the United States and Canada demonstrate behaviors characteristic of Level 2 (Sub-clinical levels of problems) or Level 3 (Disordered or pathological) gambling. (See figure below.)

Risk-taking: It’s basically a guy thing

Even though women do gamble, it’s basically a guy thing.

Risk-taking: It’s basically a guy thing. I would say that Ursula is NOT impressed. By the way, I drew this myself, and it appears in the chapter on gambling in the textbook I wrote.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that males are higher risk-takers than women, and the tendency to take risks decreases with age. Of course, there is a price to pay for this increased tendency of young men to engage in taking risks. To add insult to injury, or perhaps to fatality, Wendy Northcutt has created an institution with her Darwin Awards, given to those individuals who have discovered novel and interesting ways of removing themselves from the gene pool (Northcutt, 2003). Not surprisingly, most of the recipients of the Darwin Awards are male.

On her website, http://www.darwinawards.com , Dr. Northcutt also gives Honorable Mention to those individuals who have taken (unnecessary) risks, and have thereby ALMOST removed themselves from the gene pool. Again, most of the recipients of Honorable Mention are adolescent males. When these blokes are asked, “Why did you do it?”, whatever the “it” is, all too often the response is “I wanted to impress my girlfriend”.

Gender differences in gambling

In 1996, the Addiction Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia, conducted a study on the reasons why men and women gamble. Almost 30% of the men responded with “Excitement”. And what percentage of women gamble for “Excitement”? The answer: zero. However, women responded to the same question with 3 unique answers: 36.5% responded with “Boredom”, 31.3% with “Loneliness”, and 12.2% with “Anxiety” (Coman, et. al., 1997).

According to a study by Ibanez, et. al. (2003), women and men had different gambling preferences: women preferred playing bingo while men preferred playing slot machines. Furthermore, they found that women began betting at a later age, but the disorder progressed faster. Although male and female pathological gamblers had similar gambling severity and overall rates of psychiatric comorbidity, men had higher rates of alcohol abuse/dependence and antisocial personality disorder, while women had higher rates of affective disorders and history of physical abuse.

These findings are substantiated by those of Tavares et. al. (2001) and Tavares et. al. (2003), who differentiate between social gambling, intense gambling, and problem gambling. In their study, women started gambling significantly later in life, their periods of social gambling and problem gambling were shorter, and they preferred playing electronic bingo, and/or video lottery terminal games, i.e., games that are entirely based on chance, rather than horse racing or card games, which may involve some skill. Nonetheless, there were no differences in the age at which women and men first sought treatment.

Internet gambling

Internet gambling provides a venue that has the potential of significantly accelerating the problems caused by gambling in susceptible individuals in a manner that is unprecedented. Why? Because it provides a level of privacy and confidentiality that the casino or racetrack patron doesn’t have to deal with, making it much easier to conceal the magnitude of the problem from family, colleagues, and friends.

The risks of being trapped in pathological gambling are increased because of the privacy and ease of using a credit card that Internet gambling offer. In a study conducted by Ladd and Petry (2002), individuals agreed to fill out a questionnaire which consisted of the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) and several pertaining to their gambling habits and demographics. Granted, this was not a large, longitudinal, randomized study, but they found that the mean SOGS score of Internet gamblers was significantly higher than the mean SOGS scores of non-Internet gamblers. Over 60% of the Internet gamblers were considered Level 3 (pathological) gamblers, whereas only 10% of non-internet gamblers were at the same level.

Coman, G.J.; Burrows, G.D.; Evans, B.J. (1997). Stress and anxiety as factors in the onset of problem gambling: Implications for treatment. Stress Medicine 13:235-244.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homo_habilis#

Ibanez, A.; Blanco, C.; Morerya, P.; Saiz-Ruiz, J. (2003). Gender differences in pathological gambling. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64(3):295-301.

Ladd, G.T.; Petry, N.M. (2002). Disordered gambling among university-based medical and dental patients: A focus of internet gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 16(1):76-79.

Manus MB. Evolutionary mismatch. Evol Med Public Health. 2018 Aug 8;2018(1):190-191. doi: 10.1093/emph/eoy023. PMID: 30159142; PMCID: PMC6109377.

Northcutt, W. (2003). The Darwin Awards III: Survival of the Fittest. Dutton Books, New York.

Tavares, H.; Zilberman, M.L.; Beites, F.J.; Gentil, V. (2001). Gender differences in gambling progression. Journal of Gambling Studies 17(2):151-159.

Tavares, H.; Martins, S.S.; Lobo, D.S.S.; Silveira, C.M.; Gentil, V.; Hodgins, D.C. (2003). Factors at Play in Faster Progression for Female Pathological Gamblers: An Exploratory Analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:433-438.