I. Symptoms and Presentations of ADHD

According to a fact sheet published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neurobehavioral disorders of childhood. It is sometimes referred to as Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). It is first diagnosed in childhood and often lasts into adulthood. Children with ADHD may have trouble paying attention, controlling impulsive behaviors (may act without thinking about what the result will be), or be overly active ( https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/media/pdfs/adhdfactsheetenglish.pdf) .

A child with ADHD might show the following behaviors:

- Daydream a lot

- Forget or lose things

- Squirm or fidget

- Talk too much

- Make careless mistakes or take unnecessary risks

- Have a hard time resisting temptation

- Have trouble taking turns

- Have difficulty getting along with others.

These behaviors often manifest themselves in adulthood as well.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) lists three presentations of ADHD—Predominantly Inattentive, Hyperactive-Impulsive, and Combined (https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/adhd/what-is-adhd ).

Characteristics of Inattentive Presentation

Inattentive refers to challenges with staying on task, focusing, and organization. For a diagnosis of this type of ADHD, six (or five for individuals who are 17 years old or older) of the following symptoms occur frequently:

- Doesn’t pay close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in school or job tasks.

- Has problems staying focused on tasks or activities, such as during lectures, conversations or long reading.

- Does not seem to listen when spoken to (i.e., seems to be elsewhere).

- Does not follow through on instructions and doesn’t complete schoolwork, chores or job duties (may start tasks but quickly loses focus).

- Has problems organizing tasks and work (for instance, does not manage time well; has messy, disorganized work; misses deadlines).

- Avoids or dislikes tasks that require sustained mental effort, such as preparing reports and completing forms.

- Often loses things needed for tasks or daily life, such as school papers, books, keys, wallet, cell phone and eyeglasses.

- Is easily distracted.

- Forgets daily tasks, such as doing chores and running errands. Older teens and adults may forget to return phone calls, pay bills and keep appointments.

Characteristics of Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation

Hyperactivity refers to excessive movement such as fidgeting, excessive energy, not sitting still, and being talkative. Impulsivity refers to decisions or actions taken without thinking through the consequences. For a diagnosis of this type of ADHD, six (or five for individuals who are 17 years old or older) of the following symptoms occur frequently:

- Fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat.

- Not able to stay seated (in classroom, workplace).

- Runs about or climbs where it is inappropriate.

- Unable to play or do leisure activities quietly.

- Always “on the go,” as if driven by a motor.

- Talks too much.

- Blurts out an answer before a question has been finished (for instance may finish people’s sentences, can’t wait to speak in conversations).

- Has difficulty waiting for his or her turn, such as while waiting in line.

- Interrupts or intrudes on others (for instance, cuts into conversations, games or activities, or starts using other people’s things without permission). Older teens and adults may take over what others are doing.

Characteristics of Combined presentation

This type of ADHD is diagnosed when both criteria for both inattentive and hyperactive/impulse types are met.

II. What drives ADHD.

Jaeschke et. al. (2021) suggest “that the core clinical phenomenon related to ADHD, and the major source of condition-specific impairment, is the excessive spontaneous mind wandering.” Furthermore, they state the following:

“In plain words, individuals with ADHD are distracted primarily by their own train of thoughts, ever less relevant to the talk at hand. Mind wandering typical for ADHD can be, thus, seen as a flection of insufficient cognitive control mechanisms, overstretched by environmental demands…there are some some specific features of the ADHD-related MW (mind-wandering) making it different from ‘ordinary daydreaming’: the ineffectiveness of context regulation (i.e., the frequency of wandering thoughts is not constrained easily, regardless of the situation, perceptual decoupling (i.e., reduced capacity to respond to external sensory stimuli when ‘roaming mentally’) and a clear sense of relief while engaging in salient and rewarding activities. Mind wandering has been found to be closely related to all three dimensions of ADHD symptomatology (i.e., attention deficits, hyperactivity, and impulsivity) – as well as the corresponding emotional dysregulation. At the same time, the intensity of MW seems to be independent from the history traumatic brain injuries, substance use disorders, educational deficits, or perinatal adverse outcomes – further substantiating the idea the the phenomenon of spontaneous MW is the specific (dys)functional hub of ADHD.”

The MW hypothesis proposes that “altered interaction between the large scale networks (default mode network [DMN], executive control network, salience network and visual network), and that deficient DMN deactivation during task activities will lead to excessive spontaneous MW, lacking in coherence and topic stability, which in turn will lead to ADHD symptomatology (Jaeschke, et. al., 2021).

If such is the case, then ADHD should be considered primarily a ‘brain connectivity disorder’.

III. The psychostimulant drugs used in the treatment of ADHD

According to Bushell (2023), the three main stimulants prescribed for ADHD in Australia are dexamfetamine, methylphenidate (sold under the brand names Ritalin and Concerta) and lisdexamfetamine (sold as Vyvanse).

Dexamfetamine and methylphenidate have been around since the 1930s and 1940s respectively. Lisdexamfetamine is a newer stimulant that has been around since the late 2000s. Dexamfetamine and lisdexamfetamine are amphetamines. Lisdexamfetamine is inactive when it’s taken and actually changes into active dexamfetamine in the red blood cells. This is what’s known as a “prodrug”.

All of these drugs are Schedule II drugs, meaning “Schedule II drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with a high potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence. These drugs are also considered dangerous” ( https://www.dea.gov/drug-information/drug-scheduling ). Therefore, they must be taken with caution.

The modes of action for these psychostimulant drugs are similar, but in order to explain their modes of action, it’s worth pausing to take a look at one particular reward circuitry of the brain.

IV. The reward circuits of the brain

The neural systems which have received the most attention in terms of their effects on reward processes both animals and humans include the following:

- The mesolimbic dopaminergic system, which is of greatest importance here in the discussion of the modes of action of psychostimulants;

- The endogenous cannabinoid system; and

- The endogenous opioid system.

The components of the mesolimbic dopaminergic system connect the ventral tegmentum (VTA), located in the midbrain, to the nucleus accumbens (NA), and the prefrontal cortex, which is the executive part of the brain.

The cells of this pathway communicate with each other with each other with pulses of dopamine, which is released under two circumstances:

- A pulse of dopamine “marks” natural rewards, such as food, water, sex, and nurturing, making it more likely for an individual to seek and repeat those behaviors;

- Some studies indicate that dopamine is released in anticipation of a reward, and dopaminergic neurons reduce their firing rate, and sometimes cease their firing rate after the reward is delivered.

V. Mode of Action

The YouTube clip located at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JTQQkC23hyY will be useful to visualize the mode of action.

The cycle during which dopamine is released from the presynaptic cell, crosses the synapse, binds to receptors on the postsynaptic cell, and then is returned back into the presynaptic cell via transporters is shown in the following figure:

Methylphenidate blocks presynaptic dopamine and norepinephrine transporters, norepinephrine transporters, thereby increasing catecholamine transmission, as shown in the following figure:

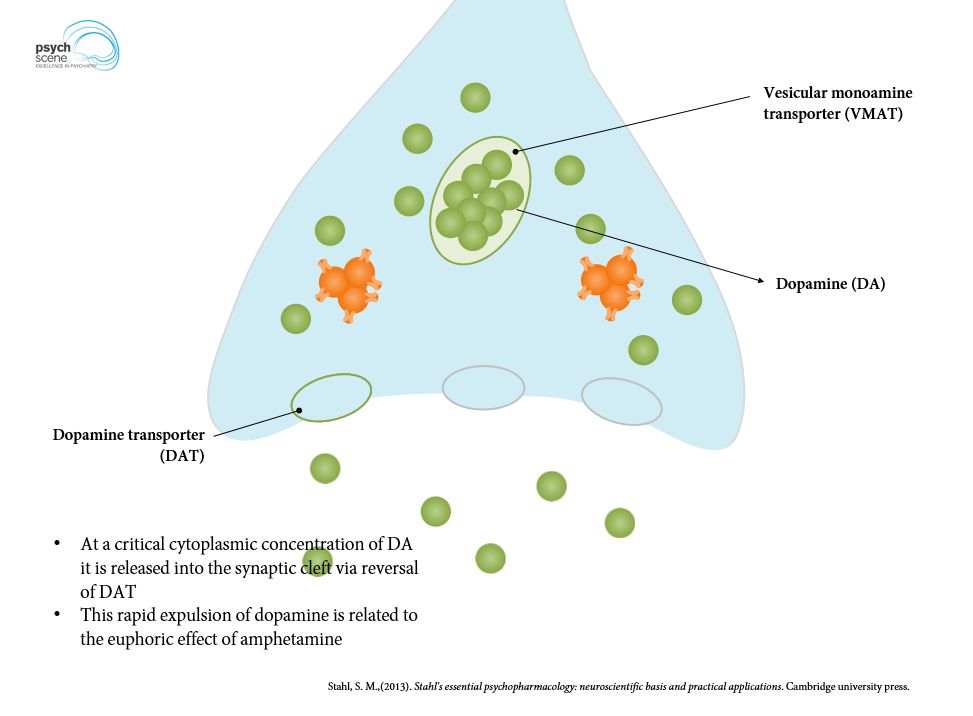

Amphetamine also inhibits both transporters, but it also increases the presynaptic efflux of dopamine.

The side-effect profiles of these drugs are similar: Appetite suppression, insomnia, dry mouth, and nausea (Posner, et. al., 2020).

Bushell, M. (2023). How do stimulants actually work to reduce ADHD symptoms? https://theconversation.com/how-do-stimulants-actually-work-to-reduce-adhd-symptoms-215801#:~:text=Stimulant%20drugs%20are%20thought%20to,between%20neurons%2C%20known%20as%20synapses.

Jaeschke, R.R.; Sujkowska, E.; Sowa-Kucma, M. (2021). Methylphenidae for attention-deficient/hyperactivity disorder in adults: a narrative review. Psychopharmacology 238:2667-2691. https//doi.org/10.1007/s00213-021-05946-0.

Posner, J.; Polanczyk, G.V.; Sonuga-Barke, E. (2020). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 395(10222): 450-462. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33004-1.