There is no doubt that the production, distribution, and sales of alcohol (and drugs) generate an enormous amount of funds. In 2017, the United Kingdom’s Institute of Alcohol Studies published SPLITTING THE BILL: ALCOHOL’S IMPACT ON

THE ECONOMY, in which alcohol’s impact on the UK economy is examined (https://www.ias.org.uk/uploads/pdf/IAS%20reports/rp23022017.pdf ).

The following are quotes from that report:

- “The alcohol industry is a small, but not insignificant, part of the UK economy, contributing £46 billion a year, around 2.5% of total GDP, to national income. This income is split evenly between the production (e.g. brewers, distillers) and retail (e.g. pubs, bars, supermarkets) of alcohol. Brewing beer for the domestic market (especially the on-trade), and distilling spirits for export are particularly significant economic activities in the UK.”

- “The UK has a small surplus in alcohol trade of £1.7 billion, almost entirely attributable to the export of spirits. However, this accounts for just 2% of the country’s overall current account deficit.”

- At the same, however: “The Government raises £11 billion in tax revenue from alcohol excise duty in England. A lack of reliable figures means it is difficult to compare this against the cost of alcohol to the taxpayer, which likely ranges between £8-12 billion.”

The consumption of alcohol brings with it enormous costs in terms of healthcare utilization, reduced workplace productivity, collisions and criminal justice. For example, the US Centers for Disease Control produced the following infographic:

From: Excessive drinking is draining America’s economy, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/excessive-drinking-is-draining-americas-economy-cdc/

The situation is similar in the United Kingdom and in Ireland, respectively:

From https://www.ias.org.uk/uploads/pdf/IAS%20reports/rp23022017.pdf , SPLITTING THE BILL: ALCOHOL’S IMPACT ON

THE ECONOMY AN INSTITUTE OF ALCOHOL STUDIES REPORT, February 2017, http://www.ias.org.uk @InstAlcStud

From: Alcohol’s cost to society, https://alcoholireland.ie/facts-about-alcohol/alcohol-cost-to-society/

The late Dr. Eugene Epstein, Ph.D., was the person who confronted me about my drinking. As he did so, I could see tears in his eyes, and even then, I understood why, because he understood how destructive alcoholism can be to the family. In a previous blog (#50 – ), I went into some detail as to how alcoholism and drug misuse have effects on ever-expanding circles of people around the user. It is not for nothing that alcoholism is described as a family disease ( https://www.al-anon-sc.org/the-family-disease-of-alcoholism.html ).

In this blog, I want to look at the economic and societal costs of substance abuse.

BLUF: (Bottom line, up front: “A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking real money.”)

————————————————————————————

I. Economic costs

The amount of money spent on alcohol, nicotine products, and illicit drugs is staggering. In 1998, revenues from the sale of cigarettes, alcohol, and illicit drugs exceeded $128.3 billion or 2.5 percent of the US GDP, and is now estimated to be $249 billion. About 11 percent of revenues from the sale of cigarettes and alcohol are used for advertising which amounts to over $10 billion a year, or $28 million a day ( https://hpi.georgetown.edu/abuse/ ) .

Most of the adverse health consequences of substance abuse result in diseases and premature deaths. About 28 percent of all deaths annually can be traced to the use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs. Of these deaths, tobacco is directly responsible for the largest share. Alcohol and illicit drugs also lead to death directly, but are more likely to contribute to a fatal accident or homicide. Death from substance abuse is more likely to occur as an adult from substance use that began in adolescence.

Ia. Tobacco

The following data regarding cost estimates for the purchase and subsequent healthcare costs are from The Cost of Cigarette Smoking: It’s Higher Than You Think, uploaded by the Moultrie County Health Department,https://www.moultriehealth.org/news/the-cost-of-cigarette-smoking-its-higher-than-you-think/:

As of April 2024, the average cost of a pack of cigarettes in Illinois was $10.16. If you smoke one pack of cigarettes each day, your monthly expense is $309.33, and your annual cost for the cigarettes themselves would be $3,708.40.

Then there are taxes, right? In Illinois, state and federal taxes would add $2.98 to that $10.16 per pack, so again, if you smoke one pack a day for For example, the per-pack cost of $10.16 includes $2.98 in state and federal taxes. At today’s prices, if you smoke one pack a day for a year, you will pay $1,088 in state and federal taxes.

The continued deposition of carbon particles covered with carcinogenic compounds, as shown below, will take its toll in terms of losses in productivity and increased healthcare utilization:

Cross-section of lung showing area occluded by carbon particles. (Ed. Note: Modesty prevents me from naming who took this photomicrograph.)

The above photo is at the microscopic histological level. With continued smoking, the difference between a lung from a healthy person and a lung from a smoker become very obvious:

Healthcare utilization among smokers is much higher than it is for non-smokers. The chart shown below is based on data presented at https://www.fisherphillips.com/en/news-insights/can-you-link-insurance-premiums-to-smoking.html, uploaded in 2014:

| Parameter | Smokers | Non-smokers |

| Hospital visits per 1,000 | 124 | 76 |

| Average length of stay in hospital (# days) | 6.5 | 5 |

| # of days work missed per year | 6.16 | 3.86 |

There are additional differences between smokers and non-smokers:

- A smoker taking four 10-minute smoke breaks actually worked one month less over the course of a year than a non-smoking employee;

- The US Centers for Disease Control estimate that each smoking employee costs a company an additional $3,391 per year – including $1,760 in lost productivity and $1,623 in excess medical expenses.

The added costs incurred by smokers has resulted in numerous state governments and private companies, such as Macy’s and PepsiCo, charging higher insurance premiums to employees who smoke, and some companies even refuse to hire smokers. Furthermore, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) by allows insurers to raise smokers’ premiums up to 50% over those paid by nonsmokers.

Ib. Alcohol

I was expecting a similar trend with alcohol, that there would be a direct relation between the amount of alcohol consumed and healthcare utilization.

To my surprise, that is not necessarily the case. Zarkin, et. al. (2004) describe a study in which all adult patients entering one of three primary care clinics were given an initial short health and lifestyle questionnaire. Those patients who exceeded the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines for moderate drinking were subsequently given a more comprehensive alcohol screening using a modified version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Using both data from AUDIT and surveys regarding the quantity of alcohol consumed and frequency of drinking, they estimated models of the relationship between drinking patterns and days of health care use, controlling for demographic characteristics and other variables.

They found that “current alcohol use is generally associated with less health care utilization relative to abstainers. This relationship holds even for heavier drinkers, although the differences are not statistically significant. With some exceptions, the overall trend is that more extensive drinking drinking patterns are associated with lower health care use.

They suggest two possible reasons for this:

- Heavy drinkers deliberately choose not to seek medical attention than abstainers;

- Perhaps this is indirect evidence that drinking some alcohol is beneficial to health.

Nonetheless, there is ample evidence that alcohol consumption is deleterious to health:

The following statistics are from Alcohol’s cost to society ( https://alcoholireland.ie/facts-about-alcohol/alcohol-cost-to-society/):

In Ireland, a cost analysis of the financial burdens of alcohol harm has not been carried out since 2014. At that time, a Department of Health commissioned analysis put the cost of alcohol harm at approximately €2.35 billion annually. This figure includes:

- Cost to the health care system €793m

- alcohol-related crime cost €686m

- alcohol-related road accidents cost €258m

- lost economic output due to alcohol €614m (€195 million due to absenteeism, €185 million due to accidents at work, €169 million due to suicide and €65 million due to premature mortality).

Since, then the OECD estimates that for Ireland the costs are of the order of about 1.9% of GDP which tallies with research cited by the World Health Organisation that in high income countries alcohol harm amounts to up 2.5% of GDP.

For Ireland that would equate to approximately €9.6bn-€12bn annually.

Against that alcohol excise duties only raise €1.2 bn annually.

It gets worse:

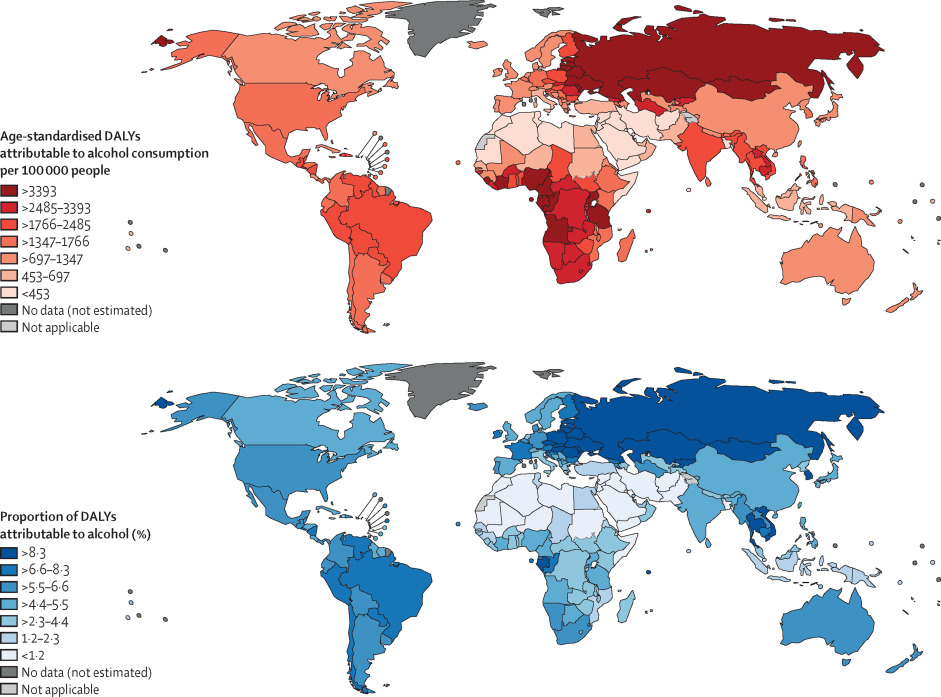

- Alcohol is the drug of abuse most consumed, causing 3 million deaths (5.3% of all deaths) worldwide and 132.6 million disability-adjusted life years (Gimenez-Gomez, et. al., 2023);

- Alcohol is involved in a substantial percentage of all hospital admissions, but the magnitude varies considerably:

- Brink (2004) states that 30 to 50% of all hospital admissions in the United States are alcohol related;

- Lange and Schacter (1989) state that the percentage of alcohol related admissions to hospitals in Manitoba, Canada was found to range from 6.38% to 14.93% on medical units;

- Gronkjaer, et. al. (2017). state that 20% of all hospital admissions in Denmark are alcohol related.

- Alcohol accounts for 66 percent of fatal accidents, 70% of homicides and 37% of suicides in the United States. Furthermore, alcohol abuse adds $23 billion to the nation’s annual medical tab (Brink, 2004);

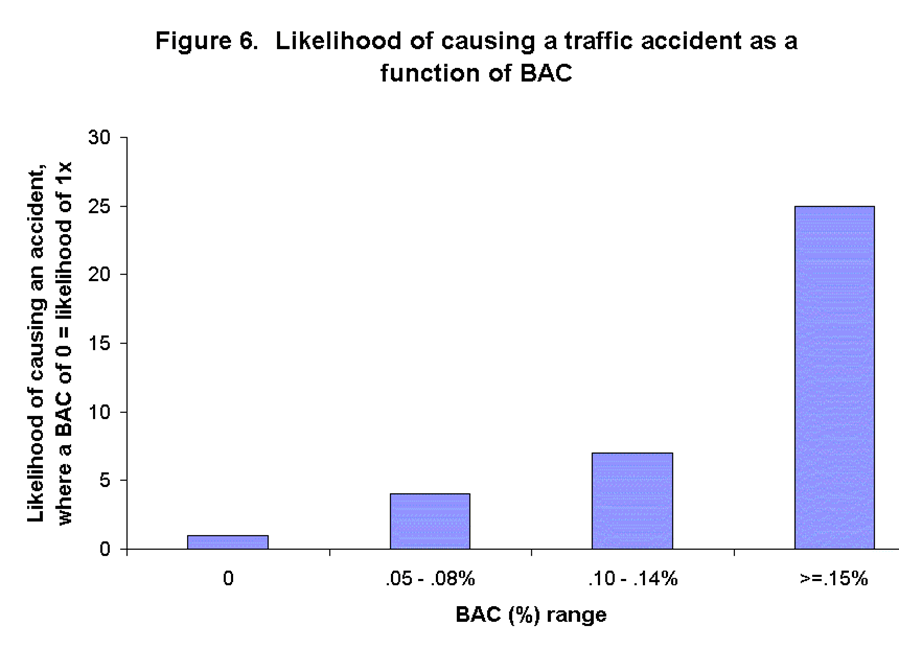

- The likelihood of being in a traffic accident is geometrically related to the amount of alcohol consumed:

Figure 6 from Eisen (2018). Men, Women, and Their Addictions: A Biological Approach.

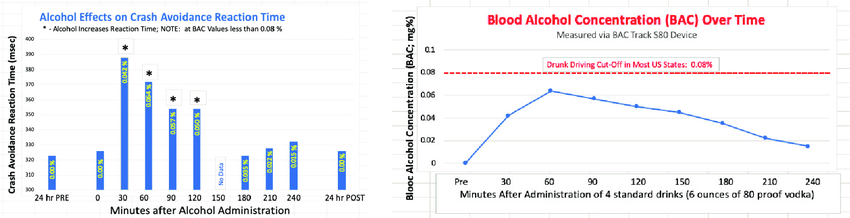

- Even at blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) less an 0.08%, alcohol will cause an increase in crash avoidance reaction time:

Figure from Zohr, et. al., (2020).

- DALYs refer to Disability-Adjusted Life Years, usually measured as the number of DALYs per100,000 individuals. DALYs are used to measure total burden of disease – both from years of life lost and years lived with a disability. One DALY equals one lost year of healthy life.

Ic. Illicit drugs

Robin Williams once said, “Cocaine is God’s way of telling you you are making too much money.”

And he’s right. According to https://www.gatewayfoundation.org/blog/cost-of-drug-addiction/#financial , a gram of cocaine costs $93. Other drugs are pricey, too:

| Drug | Price per gram | URL of source | Year of source |

| Heroin | $152 | https://www.gatewayfoundation.org/blog/cost-of-drug-addiction/#financial | N.A. |

| Methampheta-mine | $56-$81 | https://www.statista.com/statistics/942032/price-per-gram-of-methamphetamine-in-the-us/ | 2024 |

| Marijuana | From $2.60 in Los Angeles to $100 in New Orleans (!) | https://www.statista.com/statistics/943438/per-gram-marijuana-prices-in-large-us-cities/ | 2024 |

| Xylazine | Laboratory grade, from a chemical company – $267 | https://www.calpaclab.com/xylazine-1g-each/spc-x2016-1gm?srsltid=AfmBOooQLFkhw1vvn_-9GVAQL8qQo90zQEG5hP4sqjXwKJDXKDNfxYk_ | N.A. |

| Tusi | $10 | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10636235/#:~:text=Tusi%20reportedly%20now%20has%20a,aware%20of%20its%20potential%20contents. | 2024 |

| LSD | $5 to $200 | https://zinniahealth.com/substance-use/lsd/costs | 2023 |

II. Societal costs

The effects that alcohol alone has on the GDP of countries is significant:

| Country | % of GDP |

| Australia | 1.7 |

| Belgium | 0.5 |

| France | 2.1 |

| Germany | 1.1 |

| Portugal | 1.3 |

| Russian Federation | 2.1 |

| South Africa | 2.5 |

| South Korea | 1.5 |

| Spain | 0.3 |

| Sri Lanka | 1.1 |

| Sweden | 1.1 |

| Thailand | 2.0 |

Table adapted from Table 2 in Manthey, J. et. al., (2021)

That effect on the GDP can be parsed into 4 separate categories:

- Low productivity, corresponding to:

- Lost value of work due to premature deaths

- Long- and short-term disability

- Healthcare costs, corresponding to

- Hospitalizations

- Emergency visits

- Prescription drugs

- Criminal justice costs, corresponding to

- Policing

- Courts

- Correctional services

- Other direct costs, corresponding to

- Research and prevention

- Motor vehicle collision damage

- Workers compensation

And as we can see from the following chart, those separate categories can involve enormous amounts of money. In 2020, the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) and the University of Victoria’s Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research (CISUR) released a report entitled The Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms (CSUCH) ( https://csuch.ca/about/). Their report shows that as of 2020, the total cost of harms related to substance use in Canada was $49.2 billion Canadian:

| Category | Amount |

| Lost Productivity Costs | *$22.4 billion *Includes: 1) Lost value of work due to premature deaths 2) Long- and short-term disability |

| Healthcare Costs | *$13.4 billion *Includes: 1) Hospitalizations 2) Emergency visits 3) Prescription drugs |

| Criminal Justice Costs | *$10.0 billion *Includes: 1) Policing 2) Courts 3) Correctional services |

| Other Direct Costs | *$3.3 billion *Includes: 1) Research and prevention 2) Motor vehicle collision damage 3) Workers’ compensation |

In a report from the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, https://hpi.georgetown.edu/abuse/, they state:

“The societal costs of substance abuse in disease, premature death, lost productivity, theft and violence, including unwanted and unplanned sex, as well as the cost of interdiction, law enforcement, prosecution, incarceration, and probation are, however, greater than the value of the sales of these addictive substances Everyone pays for these costs. Consumers pay in the form of higher prices for goods and services. Employers and employees pay higher health insurance premiums. Taxpayers pay higher taxes for the public expenditures of health care, law enforcement, the judicial system, incarceration as well as prevention and treatment programs. The price is also reflected in the need for foster care and homeless shelters. Substance abuse also hinders economic growth and diverts resources away from future investments.”

Most of the adverse health consequences of substance abuse result in diseases and premature deaths. About 28 percent of all deaths annually can be traced to the use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs. Of these deaths, tobacco is directly responsible for the largest share. Alcohol and illicit drugs also lead to death directly, but are more likely to contribute to a fatal accident or homicide. Death from substance abuse is more likely to occur as an adult from substance use that began in adolescence.

The website also states “Substance use is big business. Revenues from the sale of cigarettes, alcohol, and illicit drugs exceeded $128.3 billion or 2.5 percent of GDP in 1998. About 11 percent of revenues from the sale of cigarettes and alcohol are used for advertising which amounts to over $10 billion a year, or $28 million a day.12

The societal costs of substance abuse in disease, premature death, lost productivity, theft and violence, including unwanted and unplanned sex, as well as the cost of interdiction, law enforcement, prosecution, incarceration, and probation are, however, greater than the value of the sales of these addictive substances. Everyone pays for these costs. Consumers pay in the form of higher prices for goods and services. Employers and employees pay higher health insurance premiums. Taxpayers pay higher taxes for the public expenditures of health care, law enforcement, the judicial system, incarceration as well as prevention and treatment programs. The price is also reflected in the need for foster care and homeless shelters. Substance abuse also hinders economic growth and diverts resources away from future investments.”

IIa. Number of Emergency Department visits in the United States

In 2023, The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) published Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN): National Estimates from Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits, which included the following data:

| Type of visit | # of Drug-Related Emergency Visits in 2023 | How does data from 2023 differ from those of 2022? |

| Alcohol-related | 3,114,472 | 3.6% decrease |

| Cannabis-related | 3,896,418 | 4.6% increase |

| Opioid-related | 881,556 | 3.7% decrease |

| Methamphetamine-related | 547,491 | 6.4% decrease |

| Cocaine-related | 354,512 | 15.1% decrease |

| Benzodiazepine-related | 192,044 | about the same |

| Polysubstance-related | 1,636,933 | N.A. |

IIb. Criminal justice and incarceration

The intended goals of criminal justice

According to Briefing Paper Seven, Incarceration of drug offenders: costs and impacts (2005), some governments have chosen to pursue law enforcement oriented domestic drug control policies that rely heavily on incarceration. The goals of incarceration include the following:

- By increasing the risks, in terms of arrest and imprisonment, faced by both high-level and street-level retail dealers, strategies aim to make illicit drugs scarce and expensive. The intention is to disrupt the market and reduce access to illicit drugs by users;

- It is hoped that fear of punishment will act as a deterrent by raising the risks, again in terms of arrest and imprisonment, of drug use and thus lead to less illicit use.

Why it may work…or not.

Incapacitation

Incarceration may work at incapacitating the sale and transfer of drugs. If drug users are in prison, they are not contributing to the illicit drug market. Furthermore, most drug sellers are also users, so the incapacitation of sellers could reduce the number of active buyers. In the United States, however, research shows that states with higher rates of drug related incarceration experienced higher, not lower, rates of drug use. Furthermore, this argument does not account for the sizeable markets within prisons. A 2003 report from the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction states that an estimated 12% – 60% of inmates housed in European prisons had used drugs during incarceration (ECMDDA, 2003).

Rehabilitation

According to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rehabilitation_(penology) , rehabilitation is the process of re-educating those who have committed a crime and preparing them to re-enter society. The goal is to address all of the underlying root causes of crime in order to decrease the rate of recidivism once inmates are released from prison.[1] It generally involves psychological approaches which target the cognitive distortions associated with specific kinds of crime committed by individual offenders, but it may also entail more general education like reading skills and career training. The goal is to re-integrate offenders back into society.

Whether rehabilitation succeeds is questionable. For example, a large-scale review of research on imprisonment in Canada showed that offenders who were imprisoned were no less likely to reoffend than those given community sentences. Furthermore, those given longer sentences were MORE likely to go back to crime. It is generally agreed that imprisonment in itself does not have a reformative effect, and that alternatives to imprisonment outside of prison can be delivered more easily, and cheaply outside of prison.

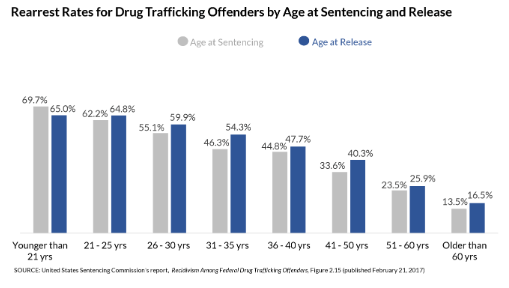

The following chart is from The United States Sentencing Commission, https://www.ussc.gov/research/research-reports/recidivism-among-federal-drug-trafficking-offenders

As opposed to these grim statistics, the Drug Treatment Alternative to Prisons programme in New York found that only 26% of offenders diverted into treatment were reconvicted, whereas 47% of comparable offenders who were sent to prison.

Deterrence

It would seem that stiff penalties for drug sales would be a deterrent, especially for low-level sellers whose sentences are disproportionately higher than for those of high-level sellers.

However, examine of the economics shows a different picture. A RAND study of the District of Columbia estimated that in 1988 street dealers faced about a 22% probability of imprisonment in the course of a year’s selling, and that given the expected amount of time served, they would spend around one-third of their selling careers in prison. You would think that such long sentences would be a deterrent, but closer examination shows that the risk per sale may be quite small. A seller who works only two days per week may make an estimated 1,000 transactions per year. Therefore, the imprisonment risk per transaction in the 1988 study could therefore by calculated to be only about 1 in 4,500.

There is general agreement that US domestic drug enforcement policies, including incarceration, has not had the desired effect of rising prices to the point that they become inhibitive to users. In fact, prices between 1980 for cocaine and heroin have declined.

Figure 1 from U.S. Drug Prices and Incarceration of Drug Law Violators (Caulkins and Chandler, Unpublished).

The United States: “The Great Incarcerator”

Bewley-Taylor, et. al. (2005 and 2007) refer to the United States as “The Great Incarcerator”, and for good reason. No other country in the world has used punitive drug control policies quite like the United States. Boyum and Reuter (2005) state that drug related arrests more than doubled, rising from 581,000 in 1980 to nearly 1.6 million in the year 2000. Of the 450,000 increase in drug arrests during the period 1990-2002, 82% of the growth was for marijuana, with 79% for marijuana possession alone. This has resulted in a substantial increase in the number of drug offence-related commitments to state and federal prison.

A 2000 Human Rights Watch stated that one in four persons imprisoned in the US was imprisoned for a drug offence, and the number of persons behind bars for drug offences was roughly the same as the entire US prison and jail population in 1980. A significant number of these individuals are admittedly non-violent offenders.

The net result of this continued use of incarceration as a drug policy in the United States is that the incarceration rate (per 100,000 of national population is, well, astounding:

| Country | Total Prison Population | Incarceration Rate (per 100,000 national population) | Drug offenders (trafficking/ dealing and possession) as proportion of total prison population |

| France | 59,655 | 96 | 13.6% |

| Germany | 73,203 | 89 | 14.9% |

| Ireland | 3,653 | 81 | 14.4% |

| UK: England and Wales | 82,240 | 151 | 15.5% |

| Russian Federation | 887,723 | 626 | 9.3% |

| United States | 2,293,000 | 756 | 19.5% sentenced state prisoners (2005), 53% federal sentenced prisoners (2007) |

It is expensive

At the time of writing of Beckley Briefing Paper Number Seven, referenced below, US Federal spending on drug control in 2002 totaled $18.8 billion. In 2008, Harvard economist Jeffrey Miron (Miron, 2008) estimated that $12.3 billion was spent keeping State and Federal drug law offenders in prison in 2006. Stated another way, the cost of placing a person in prison for a year was more than the cost of tuition, room and board at Harvard University.

The following chart of annual operating expenditures per prisoner, indexed to US dollars in 2016, is adapted from Table 4 of Sridhar, et. al., 2018:

It is risky to the health of the incarcerated

Any time that human beings are crowded into a small area, the likelihood of disease outbreaks increases, and such is the case with individuals who are incarcerated. Weinbaum et. al. (2005) report that the prevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV among persons incarcerated in US prisons is two to ten times higher than in the general population. Although these infections are largely due to sex- and drug-related risk behaviors practiced outside the correctional setting, the transmission of these infections inside jails and prisons has also been documented. Outbreaks of tuberculosis, influenza (types A and B), varicella, measles, mumps, adenovirus and COVID-19 in high-income countries (Beaudry, et. al. 2020).

In fact, the main reason why Portugal launched a groundbreaking and comprehensive drug decriminalization program in 2001 was because Portugal had the highest rate of drug-related AIDS in the European Union, the second highest prevalence of HIV among people who inject drugs, and drug overdose deaths were rapidly increasing (Drug Policy Alliance, 2023). This will be the next topic covered in this blog.

Portugal’s experiment in decriminalization

In the 1990’s, Portugal faced a healthcare crisis, with one of the highest prevalence rates for overdose deaths and problematic drug use in Europe, with people who inject heroin comprising 60% of the HIV-positive population in the country. In 1997, the Portuguese public ranked drug-related issues as the main social problem.

The government appointed a panel of doctors, lawyers, psychologist and social activists to study the problem and make recommendations for a national response. This panel recommended the following:

- To end the criminalization of people who use drugs, regardless of what drug they are using;

- To initiate having honest discussions on prevention and education;

- To provide access to evidence-based, voluntary treatment programs;

- To adopt harm reduction practices; and

- To invest in the social reintegration of people with drug dependence.

Drug trafficking can incur a sentence of one to 12 years in prison, depending on the type of substance, the quantity, cooperation with authorities, and whether the person is selling drugs to finance their addiction. In “aggravating circumstances”, which include trafficking as part of a criminal organization and if the offense causes death or serious bodily harm, drug trafficking sentences can increase to 25 years.

Since Portugal ceased criminalizing drug use, the number of people voluntarily entering treatment has increased significantly, overdose deaths decreased by over 80%, the prevalence rate of people who use drugs that account for new HIV/AIDS diagnoses fell from 52% to 6%, and incarceration for drug-related offenses decreased by over 40%.

IIc. Treatment is less expensive than incarceration

In a study funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the cost per person per year of outpatient treatment for cocaine or heroin in was about $3,100. Residential treatment for cocaine was about $12,500. Untreated addictions, however, were estimated to cost $43,200 per year per person, mostly due to the cost of incarceration ($39,600 per year per person) (see Figure 2) (https://hpi.georgetown.edu/abuse/):

That assertion is further substantiated by data presented in https://sanalake.com/addiction-resources/drug-treatment-vs-incarceration-2/ (Date of upload is unknown):

- The average cost per inmate in the United States is over $33,000, while the cost of rehab averages around $5,000;

- If 10% of offenders are sentenced to drug treatment vs. incarceration, it saves the judicial system almost $5 billion;

- Choosing treatment leads to fewer crimes, lower addiction rates, and saves society money.

IId. Maybe individuals suffering from addiction should be “sentenced” to treatment, rather than incarceration?

There are over 2 million Americans in jail right now, which equals about 1 in 100 adults in state and federal prisons and local jails. Of those, 20 percent or 1 in 5 are nonviolent drug offenders.

The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse states 65 percent of the prison population meets the criteria for substance use disorder. However, less than 11 percent receive treatment. As a result, they come out of jail without the tools and knowledge to live a life of recovery.

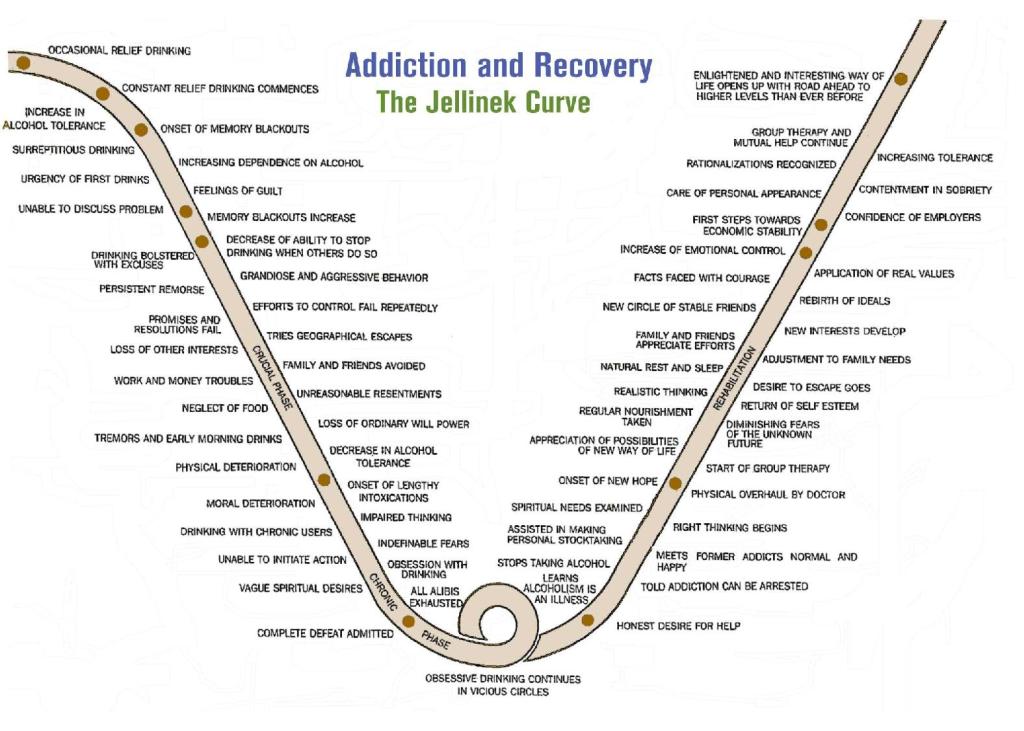

The punitive aspect of incarceration as it is practiced in the United States does not lend itself to a restoration of self-esteem and an attitude of looking forward to each day, as suggested in this diagram, called the “Jellinek Curve”:

The Encouraging News

In a May 15, 2024 press release entitled “U.S. Overdose Deaths Decrease in 2023, First Time Since 2018”, the US Center for Disease Control’s National Center for Health Statistics stated the following:

Provisional data from CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics indicate there were an estimated 107,543 drug overdose deaths in the United States during 2023—a decrease of 3% from the 111,029 deaths estimated in 2022. This is the first annual decrease in drug overdose deaths since 2018…The new data show overdose deaths involving opioids decreased from an estimated 84,181 in 2022 to 81,083 in 2023. While overdose deaths from synthetic opioids (primarily fentanyl) decreased in 2023 compared to 2022, cocaine and psychostimulants (like methamphetamine) increased.”

And here is the accompanying table:

P.S.:

P.P.S.: About that picture I showed at the beginning of a wrecked car:

There’s a reason why I selected this particular image to show a car wreck. The car belonged to the older daughter of Dave Brown, meteorologist in Memphis, TN, whose younger daughter was going to be married the next day. They were going to have a celebratory dinner on the day prior to the wedding, but they were missing some groceries, so the older daughter, married and pregnant, offered to go to the store and buy the necessary food. She took her child (a 2-year old daughter named Zadie) with her to the store.

She never made it there. She was struck by a drunk driver who did not apply his brakes. Police estimate that this driver, who survived and is now in prison, was driving 120 mph at the moment of impact. Ten years after the collision, police and neighbors were still finding fragments of steel at the collision site. The car you see was then put on a flat-bed truck and taken around the United States to show the effects of drunk driving.

There’s more to the story, but that’s enough.

Beaudry G, Zhong S, Whiting D, et. al. (2020). Managing outbreaks of highly contagious diseases in prisons: a systematic review. BMJ Global Health 2020;5:e003201. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003201

Bewley-Taylor, D.; Trace, M.; Stevens, A. (June 2005). Incarceration of drug offenders: costs and impacts. Beckley Foundation Drug Policy Foundation Drug Policy Programme, Briefing Paper Seven.

Bewley-Taylor, D.; Hallam, C.; Allen, R. (March 2009). The Incarceration of Drug Offenders. Beckley Foundation Drug Policy Foundation Drug Policy Programme, Briefing Paper Sixteen.

Boyum, D.; Reuter, P. (2005). An Analytic Assessment of US Drug Policy. Washington, DC, The AEI Press.

Center for Disease Control (May 15, 2024). U.S. Overdose Deaths Decrease in 2023, First Time Since 2018. (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2024/20240515.htm#:~:text=Provisional%20data%20from%20CDC’s%20National,drug%20overdose%20deaths%20since%202018).

Drug Policy Alliance. (2023). Drug Decriminalization in Portugal: Learning from a Health and Human-Centered Approach. A Drug Policy Alliance Release, http://www.drugpolicy.org.

EMCDDA (2003). Annual Report 2004. State of the Drugs Problem in the European Union and Norway. Lisboa, Portugal: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.

Gimenez-Gomez, P.; Lee, T.; Martin, G.E. (2023). Modulation of neuronal excitability by binge alcohol drinking. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. Feb 14;16:1098211. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2023.1098211 .

Gronkjaer, M.; Sondergaard, L.N.; Klit, M.O.; Mariegaard, K.; Kusk, K.H. (2017). Alcohol screening in North Denmark Region hospitals: Frequency of screening and experiences of health professionals. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 34(3)230-242. DOI: 10.1177/1455072517691057

Lange, D.E.; Schacter, B. (1989). Prevalence of alcohol related admissions to general medical units. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 19(4):371-387. doi: 10.2190/b8tq-Seg9-fht8-uvxl.

Luangsinsiri, C.; Youngkong, S.; Chaikledkaew, U.; Poaatanaprateep, O.; Thavorncharoensap (2023). Economic costs of alcohol consumption in Thailand, 2021. Global Health Research and Policy 8:51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-023-00335-w.

Sridhar, S.; Cornish, R.; Fazel, S. (2018). The Costs of Healthcare in Prison and Custody: Systematic Review of Current Estimates and Proposed Guidelines for Future Reporting. Frontiers in Psychiatry 9:1-9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00716.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2024). Drug Abuse Warning Network: National

Estimates from Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits, 2023. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data.

Weinbaum, C.M.; Sabin, K.M.; Santibanez, S.S. (2005). Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV in correctional populations: a review of epidemiology and prevention. AIDS 19():p S41-S46, October 2005. | DOI: 10.1097/01.aids.0000192069.95819.aa

Zarkin, G.A.; Bray, J.W.; Babor, T.F.; Higgins-Biddle, J.C. (2004). Alcohol Drinking Patterns and Health Care Utilization in a Managed Care Organization. HSR: Health Services Research 39(3):553-569.

Zohr T, Nwobi E, Zada TM, Andrews J, Commissaris R, et al. (2020) Wake Up America and Save Lives!!! Move the Drunk Driving Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) Cut-off to 0.05%!!! J Addict Med Ther Sci 6(1): 077-081. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.17352/2455-3484.000044