One may argue that a (psychoactive) drug is a drug is a drug, but drugs may differ in terms of their impact on society, and particularly on the magnitude of violence on that society.

I. Alcohol

This is a story that I’ve mentioned once before:

Back around 1996, when states including Colorado and California were considering the legalization of cannabis for both medical and for recreational use, I had a conversation with a Memphis (TN) police officer at an exercise center, during which I asked him what he thought about whether marijuana should be legalized in Tennessee.

His response, “ABSOLUTELY!!”, was so quick and adamant that I was taken aback, so I asked him, “How so?”

He started with “When was the last time I had to break up a fight between two drunks? Like, at 3 a.m. this morning…“

He then continued: “And when was the last time I had to break up a fight between two potheads? Like, NEVER.”

The majority of previous posts to this blog have dealt with the effects of drugs on the individual. In this blogpost, we will look at the effects of alcohol and drugs on society. To do so, I will be extensively using a report dated 2017-2018 entitled Alcohol and Violence, part of the Alcohol and Society Research Report Series, produced by an international group of medical and public health researchers from Canada, Australia, the United States, and Sweden. This report, authored by Andreasson, et. al. (2017-2018) describes the close correlation between alcohol consumption by both perpetrators and victims with the frequency of violent acts. They also suggest possible mechanisms for this correlation between alcohol consumption and violence.

A. Violence rates vary with alcohol consumption

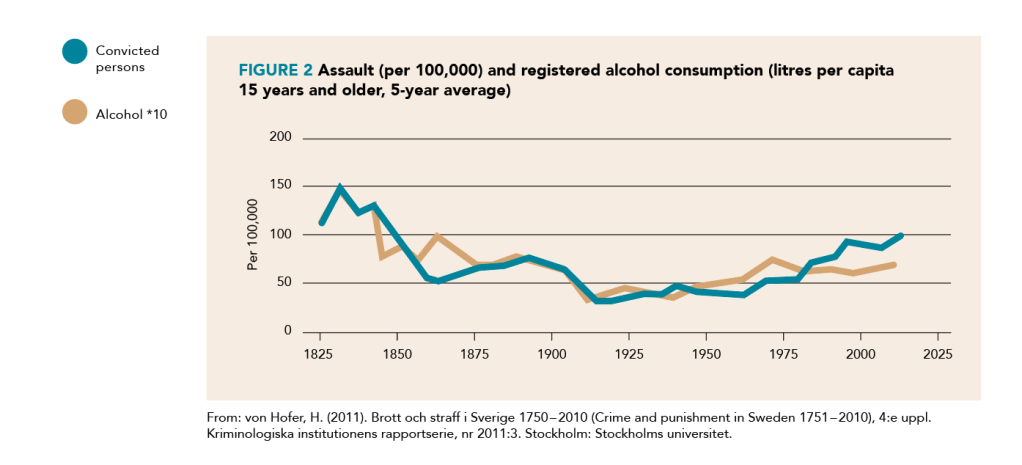

According to Andreasson, et. al. (2017-2018), official national records from Sweden show that rates of both homicide (Figure 1) and assault (Figure 2) closely followed rates of per capita alcohol consumption over the years from 1851 to 2009.

For the sake of comparison, contrast the following figure of alcohol consumption in the Unites States with Figure 1, shown above:

Furthermore, there is a correlation between violence and alcohol consumption by both perpetrators and victims:

B. What is it about alcohol consumption that drives violence?

By way of introduction, let’s take a look at the following infographic, which shows the effects of alcohol on the brain before we address the specific issue of alcohol consumption and violence:

We can get an understanding of alcohol’s role in violence from three approaches:

- Experimental laboratory studies of humans and animals;

- Epidemiological studies of the relationship between alcohol consumption and violence;

- Epidemiological studies of policy interventions or natural experiments that result in changes to alcohol consumption.

a. What experimental laboratory studies of humans and animals show us:

Laboratory studies have explored at least three possible pathways by which alcohol use may cause aggression:

- We know that alcohol use impairs working memory, planning, and response inhibition. With the consumption of alcohol, the innate aggressiveness usually suppressed by inhibitory functions of the brain is disinhibited. Even within the limited range of alcohol doses in laboratory drinking experiments, dose-response effects have been demonstrated to show that aggressive behavior is even more likely with higher doses of alcohol. (In other words, the frontal lobe is our friend. FA with it, and FO*);

- Although learned beliefs about alcohol and aggressive behavior, sometimes referred to as ‘expectancies’ show a small to negligent effect on aggression, expectancies may work synergistically with pharmacological effects to increase the likelihood of aggressive acts particularly in relation to sexual violence. In some experimental drinking studies, verbal vignettes, videotapes or audiotapes describing date rate scenarios have been used, and have shown that the pharmacological effects of alcohol on sexual aggression are real and are associated with misperceptions of sexual arousal, sexual cues and willingness of the victim. Individual characteristics of study participants also predict their responses such as sexual dominance and hostility towards women. Furthermore, a review by Gidycz, et. al. (2006) has shown that when women exposed to alcohol, placebo and no alcohol were compared, the alcohol groups perceived fewer negative outcomes of engaging in behavior with intoxicated males and gave less attention to cues that were indicative of sexual assault risk. Interestingly, women given placebos also anticipated that they would be more likely to engage in risky behaviors when drinking, suggesting an expectancy effect;

- The pharmacological effects of alcohol cause additional cognitive, emotional and physiological changes that are made more or less likely to result in aggression depending on external forces. Thus, the effects of alcohol in this view are indirect.

To make a long story short, therefore, the frontal cortex is our friend. FA with it, and FO* what might happen:

*FAFO is the acronym for “Fuck Around and Find Out.”

b. What we learn from epidemiological studies of the relationship between alcohol consumption and violence:

Levels of alcohol use in the general population have been shown to predict the risks of involvement in violence. For example, Norström (2001) found that a reduction in consumption of 1 litre of pure alcohol per capita per year in Europe was associated with a 7% reduction in homicides. At the same time Swedish studies found that a 1 litre increase in consumption was associated with a 7% increase in assaults from 1960 – 1994 (Andreasson,et. al., 2006) , and a 10.2% increase in assaults from 1987 – 2015 (Stockwell, et. al., 2017). Finally, a study from Norway from 1911 to 2003 (Bye, 2007) found that an increase in alcohol consumption of 1 litre per year per inhabitant predicted a change of approximately 8% in the rate of violent crimes.

c. What we learn from epidemiological studies of policy interventions or natural experiments that result in changes to alcohol consumption.

The incidence and frequency of violent acts have been linked to societal policies, such as decreased alcohol prices, extended trading hours (i.e., hours of sale), decreased minimum age to purchase alcohol; and increased alcohol outlet density, including both on- (e.g., taverns, hotels, bars, pubs, and clubs) and off-premise outlets (e.g., retail stores, off sales). Conversely, studies of reduced availability and increased alcohol prices have found evidence of reduced rates of violence.

C. Social and economic costs of violence

From Andreasson, et. al., (2017-2018): “The economic costs of alcohol-related violence include direct costs such as those to the healthcare system, the policing and legal/criminal justice services, and costs to support victims (e.g., providing refuge). Indirect costs include work and school absenteeism and lost productivity among those who continue to attend work and school. The burden of alcohol-related violence on public service provision and the economy can be immense. For health and criminal justice agencies, apprehending and treating offenders and victims of alcohol-related violence is financially costly and diverts resources from other health and crime issues. Furthermore, health and judicial staff can frequently be victims of alcohol-related violence themselves while at work, and this may encourage employees to consider alternative careers.”

D. Alcohol’s role in sexual violence

(The above figure is from https://verdevalleysanctuary.org/end-sexual-assault/ )

Abbey (2011) states that although intoxication is not a prerequisite for sexual violence, these two phenomena frequently co-occur, suggesting that alcohol may play a causal role in some sexual assaults. There are 3 possible explanations for the consistent association of these two phenomena:

- Alcohol consumption may be a cause of sexual aggression;

- The desire to commit sexual aggression may be a cause of alcohol consumption;

- The relationship is spurious, but rather due to a third variable that causes both drinking and sexual aggression, such as the personality trait of impulsivity.

The mechanisms by which alcohol consumption will increase the likelihood of sexual violence perpetration are pharmacological and psychological:

- Pharmacological effects of alcohol consumption: Acute alcohol consumption impairs multiple cognitive functions, “including episodic and working memory, abstract reasoning, set shifting, planning and judgment. Intoxication will suppress those cues which may inhibit sexually aggressive behavior, such as a sense of morality, empathy for the victim, and concern for future consequences (Abbey, 2011);

- Psychological effects of alcohol consumption: Intoxication provides an excuse for disinhibited behavior. Hence, an intoxicated man is likely to assume that anyone willing to dance is also willing to have sex. Furthermore, many men believe that alcohol makes women more responsive to sexual invitations, and they know that intoxicated women will be easier targets.

In her article, Abbey poses an interesting question: Do perpetrators who use the victim’s intoxication to obtain sex have unique attributes? She refers to several studies which address this question:

- Tyler et. al. (1998) found that the use of alcohol or drugs to incapacitate the victim was positively associated with usual alcohol consumption and favorable attitudes about casual sex;

- Abbey and Jacques-Tiura (2011) described the findings from a community sample of 457 young, single men. Perpetrators who used verbal coercion to obtain sex, perpetrators who used the victim’s impairment to obtain sex, and non-perpetrators were compared on a wide range of common risk factors. As compared to non-perpetrators, both groups of perpetrators were more hostile toward women, had more positive attitudes about casual sex, had lower empathy, engaged in more delinquent behaviors, and had more drinking problems. For all these variables except attitudes about casual sex, perpetrators who used the victim’s impairment as their tactic also had more extreme scores than did perpetrators who used verbal coercion as their primary tactic.

II. Cocaine

Cocaine users show a number of neuropsychological impairments, all of which could lead to violent behavior (Romero-Martínez and Moya-Albiol, 2015):

- Empathy: Individuals who are dependent on cocaine have empathy-related deficits, particularly in perspective-taking, emotional decoding and emotional empathy. Furthermore, they present high levels of alexithymia, i.e., the inability to identify and verbalize their own emotions;

- Executive functioning: Chronic use of cocaine is related to poorer executive functioning, affecting capacity for inhibition, mental flexibility, planning ability, alternation of cognitive sets and decision-making. Executive functions are critical for good social adaptation, so that deficits in these mental processes facilitate the expression of violence;

- Memory: Several studies have revealed that adult cocaine users have deficits in memory, both immediate and delayed. They also have working memory deficits, whose functions provide the foundation for other high-level cognitive processes, such as executive functioning. With regard to the relationship between cocaine use, memory deficits and violence, only one study has analyzed it in adults, reporting that in heterosexual couples with a history of polysubstance abuse (cocaine included), the greater the deficit in the delayed recollection of words in the California Verbal Learning Test, the poorer the recollection of episodes of violence against their partners (Medina, Schafer, Shear, & Armstrong, 2004). Therefore, there is no direct relationship between memory deficits and violence; rather, deficits in delayed recall could more likely associated with deficits in executive functioning, which in turn could be more strongly related to the expression of violence;

- Attention: Several studies have revealed that cocaine abuse in adults is related to deficits in sustained attention and problems for fixating and shifting attentional focus.

Generally, the relationship between the use and/or abuse of cocaine and violence is more evident in men than in women, as men are more prone to being physically aggressive in general and against women in particular. In women, the aggression is verbal, and is usually directed at her offspring. In both men and women the relationship between antisocial personality disorder and aggressive behavior is clearer when there is abuse of substances, such as cocaine. With regard to the concurrent use of cocaine and alcohol, the risk of displaying violent behavior and an increase in violent thoughts is greater than that produced by the separate effects of each one of these substances. This could be explained by the fact that the combination of the two substances can lead to the formation of a metabolite called cocaethylene, which inhibits the reuptake of dopamine in the systems of impulse control, such as the nucleus accumbens.

III. Alcohol, drugs and firearms

There are numerous articles which demonstrate a clear association between the consumption of either alcohol or illicit drugs and the risk of firearm violence.

For example, in a population-based, case-control study of 13- to 20-year-old residents of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Hohl et. al. (2017) found that almost all adolescent homicides were firearm homicides. The purpose of their study was to determine the relationships between exposures to drugs and alcohol at the individual, family, and neighborhood levels and adolescent firearm homicide and to inform new approaches to preventing firearm violence.

What they found was that drug use at all 3 levels and alcohol at the individual and neighborhood levels were associated with increased odds of adolescent firearm homicide:

- Adolescents with a history of alcohol use or drug use;

- Adolescents whose caregiver had a history of drug use;

- Adolescents in neighborhoods with high densities of alcohol outlets and moderate or high drug availability.

P.S.:

Abbey, A. (2011). Alcohol’s Role in Sexual Violence Perpetration: Theoretical Explanations, Existing Evidence, and Future Directions. Drg Alcohol Rev. 30(5):481-489. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00296.x.

Abbey, A.; Jacques-Tiura, A.J. (2011). Sexual assault perpetrators’ tactics: Associations with their personal characteristics and aspects of the incident. J Interpers Violence.26(14):2866-89. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390955

Andreasson, S., Holder, H. D., Norström, T., Osterberg, E. & Rossow, I. (2006). Estimates of harm associated with changes in Swedish alcohol policy: results from past and present estimates. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 101(8), 1096–105.

Andreasson, S.; Chikritzhs, T.; Dangardt, F.; Holder, H.; Naimi,T.; Stockwell, T. (2017-2018). Alcohol and violence, Alcohol and Society Research Report Series, https://alcoholandsociety.report/written-reports/alcohol-and-violence/#9223372036854775807

Bye, E. K. (2007). Alcohol and violence: use of possible confounders in a time-series analysis. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 102(3), 369–76.

Gidycz, C. A., McNamara, J. R., & Edwards, K. M. (2006). Women’s risk perception and sexual victimization: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(5), 441-456.

Hohl, B.C.; Wiley, S.; Wiebe, D.J.; Culyba, A.J.; Drake, R.; Branas, C.C. (2017). Association of Drug and Alcohol Use With Adolescent Firearm Homicide at Individual, Family, and Neighborhood Levels. JAMA Intern Med. 177(3):317-324. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8180

McGinty, E.E.; D. W. (2016). The Roles of Alcohol and Drugs in Firearm Violence. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):324-325. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8192

Medina, K.L., Schafer, J., Shear, P.K., & Armstrong, T.G. (2004). Memory ability is associated with disagreement about the most recent conflict in polysubstance abusing couples. Journal of Family Violence, 19, 381-390. doi: 10.1007/s10896-004-0683-8.

Norström T. (2001). Per capita alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality in 14 European countries. Addiction. 96(1s1):113-28.

Romero-Martínez, A.; Moya-Albiol, L. (2015). Neuropsychological impairments associated with the relation between cocaine abuse and violence: neurological facilitation mechanisms. Adicciones 27(1):64-74.

Stockwell, T., Norström, T., Angus, C., Sherk, A., Ramstedt, M., Andréasson, S., Chikritzhs, T., Gripenberg, J., Holder, H., Holmes, J. & Mäkelä, P. (2017). What are the public health and safety benefits of the Swedish government alcohol monopoly? Victoria, BC: Centre for Addictions Research of BC, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada.

Tyler, K.A.; Hoyt, D.R.; Whitbeck, L.B. Coercive sexual strategies. Viol. Victims 13:47-61.