According to wikipedia.com, the term “microbiome” is defined as “the community of organisms that can usually be found together in any given habitat.”

Included in our microbiome are a plethora of organisms, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, algae, and small protists. Some schema also include viruses and phages.

Actually, each human being has several microbiomes, located on or in different parts of the body:

The one that I will discuss in this blog is the gut microbiome, since it serves as the gut-brain axis, and is sensitive to degradation by alcohol and drugs. This gut microbiome plays many specific functions in host nutrient metabolism, maintenance of structural integrity of the gut mucosal barrier, immunomodulation, and protection against pathogens.

I. The gut microbiome is very large in both numbers, species diversity, and mass

With the use of gene sequencing methods, over 2,100 species have been isolated from human beings (Hugon, et. al., 2015). Most are anaerobic, but a few are aerobic. The aerobic species can survive in the anaerobic environment of the gut by the “leakage” of oxygen from intestinal tissue towards the lumen. These species can be divided into 4 phyla, including the Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia, with Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes representing 90% of gut microbiota (Rinnilella, et. al., 2019).

The approximate number of bacteria composing the gut microbiota is about 1013–1014 (10,000 to 100,000 billion), and can weigh anywhere between 1 and 2.5 kg.

This arrangement constitutes more than just commensalism, in which only one of the species gains from the arrangement while the other is neutral. Instead, this arrangement between (mostly) bacterial fauna and its human host can be considered an example of mutualism, in which both parties gain. The bacteria gain because they receive nutrients excreted by the gastrointestinal tract, thereby providing food. The human gains because these bacteria perform a number of essential functions:

- They secrete essential short-chain fatty acids, such as propionate, acetate, and butyrate;

- They prevent bacterial invasion by maintaining intestinal epithelium integrity;

- They are involved in the extraction, synthesis and absorption of many nutrients and metabolites, including bile acids, lipids, amino acids, and vitamins;

- They prevent the colonization of the gut by pathogenic microbes by secreting bacteriocins.

II. Factors which will influence the specific species comprising the microbiome and the magnitude of individual species

A. Age: In a study of 367 healthy Japanese subjects between the ages of 0 and 104 years, Odamaki, et. al., (2016) found that distinctly different microbiome species distributions among infants, adults, and elderly individuals.

1. Types of delivery: At birth, the intestine is sterile. However, as part of the birthing process, the newborn will acquire bacteria. If the newborn has a vaginal delivery, (s)he will acquire a microbiota composition resembling its mother’s vaginal microbiota, characterized by Lactobacillus, Prevotella, Sneathia, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifodobacterium catenulatum, Escherichia coli, Stphylococcus, bacteroides fragilis, and Streptococcus. In contrast, infants born by C-section acquire bacteria derived from the hospital environment, including Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Propionibacterium spp. Interestingly, Cesarean birth has been associated with an increased risk of chronic immune disorders such as ashtma, juvenile arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBS), and obesity (Rinnilella, et. al., 2019).

2. Methods of Milk Feeding: Breastfed babies develop a richer diversity of beneficial gut bacteria, particularly of Bifidobacterium spp. This genus of bacteria is responsible for the fermentation of galactooligosaccharide (GOS), a component of breast milk, to produce essential short chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

3. Weaning: Major gut microbiota changes occur at this point with the introduction of solid foods and the termination of milk feeding. The introduction of high-fiber and carbohydrate foods (traditional foods) causes an increase in Firmicutes and Prevotella, whereas the introduction of high-fiber and animal protein foods causes an increase in Bacteroidetes.

4. Maturation: Microbiota diversity generally increases with age until it becomes a stable adult microbiota composition dominated by the Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria. At approximately three years of age, a child’s gut microbiota composition and diversity are most like those of adults.

The typical Western diet is relatively rich in processed food full of fat and sugars, and with a low amount of fiber. This type of diet tends to reduce the diversity of bacteria in the microbiome, whereas a diet with plants and fish is positively associated with beneficial bacteria which secrete short-chain fatty acids (Praagh and Havenga, 2023). Generally, therefore, “a diverse diet high in fiber and low in processed foods is beneficial to maintaining a microbiome with increased diversity and resiliency” (Hills, et. al. 2019).;

Among people over the age of 70, gut microbiota composition can be affected by changes in digestion and nutrient absorption and by immune activity weakness. The elderly tend to have a more monotonous diet, so this, too, will weaken microbiota diversity.

B. Antibiotics: This issue is relevant when a patient is facing surgery, in which the surgeon or attending physician will prescribe antibiotics to prevent infection. Most modern antibiotics are broad spectrum, and will, therefore, have a deleterious effect on the gut microbiome, leading to gastrointestinal distress or worse. This can be reversed, or treated, with the use of probiotics, live organisms which confer a health benefit on the host, or prebiotics, food ingredients that stimulate the growth or activity of selective bacterial types in the colon;

C. Exercise: Exercise leads to an increased diversity of the gut microbiome (Clark, et. al., 2014). Daily exercise enriches the diversity of species belong to the Firmicutes phylum: Clostridiales, Roseburia, Lachnospiraceae, and Erysipelotrichaeae. These beneficial genera produce more short chain fatty acids, which in turn, heighten resistance of the intestinal barrier, reduce mucosal permeability, and inhibit the secretion of inflammatory cytokines.

III. Identifying the bacteria in the microbiome

In the past, the manner in which bacteria were identified was by culturing them. However, most bacteria in the microbiome cannot be cultured, so the genera and phyla of bacteria in the gut have been identified by identifying their genes with the more modern techniques of polymerase chain reactions, in which genes are amplified, and of 16s ribosomal RNA analysis.

The species represented in the gut microbiome include the following (Table adapted from data in Jandhyala, et. al., [2015]):

| Species found in stool samples | Species detected in the mucus layer and epithelial crypts of the small intestine |

| Bacteroides | Clostridium |

| Bifidobacterium | Lactobacillus |

| Streptococcus | Enterococcus |

| Enterobacteriacae | Akkermansia |

| Enterococcus | |

| Clostridium | |

| Lactobacillus | |

| Ruminococcus |

Microbiomes with high diversity are associated with human health and with living a long and healthy life. We find that the consumption of alcohol or drugs will reduce the diversity of microbes and allow for the introduction of pathogenic bacteria into the microbiome.

IV. Alcohol and other substances of abuse will affect the microbiome in deleterious ways

A. Alcohol

Briefly, this infographic shows what alcohol does:

The consumption of alcohol causes changes in bacterial numbers and dysbiosis (Engen, et. al., 2015). For example, alcoholics tend to show a reduction in Bacteroidetes and a simultaneous increase in Proteobacteria. The dysbiotic microbiota correlates with a high level of endotoxin in the blood, “indicating that dysbiosis may contribute to intestinal hyperpermeability and/or the increased translocation of gram-negative microbial bacterial products from the intestinal lumen into systemic circulation (Mutlu et. al., 2009; Rimola, 1991).

Although alcohol can cause intestinal dysbiosis, those alcoholic beverages that contain polyphenols, particularly red wines may favorably alter the microbiota community composition. Queipo-Ortuno (et. al., 2010) studied the microbiota in human health control subjects who consumed red wine (272 ml per day), de-alcoholized red wine (272 ml per day) or gin (100 ml per day) for 20 days and found that red wine polyphenol significantly increases the abundance of Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes, whereas gin consumption significantly decreased these same phyla. De-alcoholized red wine consumption significantly increased Fusobacteria, and gin consumption increased Clostridium abundance compared with de-alcoholized and red wine.

Alcohol disrupts the intestinal barrier and promotes intestinal hyperpermeability by a number of mechanisms. When that happens, proinflammatory/pathogenic microbial products, including endotoxin, can translocate from the intestinal lumen to the liver via the portal vein. This, in turn, will cause inflammation in the liver, which can lead to ALD (Salavrakos, et. al., 2021) and cirrhosis.

Alcohol-induced intestinal dysbiosis and its consequences may be reversible with probiotic and synbiotic interventions. Probiotics are live microorganisms taken by the host that have beneficial effects on the host beyond their simple nutritive value. Synbiotics are a combination of probiotics and prebiotics – nondigestible fibrous compounds, such as oats, that stimulate the growth and activity of beneficial bacteria in the large intestine.

B. Opioids

Opioids can alter the composition of the gut microbiome by two mechanisms:

- They induce constipation by activating mu-opioid receptors in the gut, thereby lengthening the transit time of gut contents;

- Opioid users tend to increase their intake of foods high in sugar

The dysbiosis induced by chronic opioid use is linked to central opioid tolerance, acceleration of disease progression, and immune modulation (Simpson, et. al., 2021).

Compared to controls, opioid users show a decrease in Actinobacteria, Bifidobacteriales, Lacbacillales, Dialister, Paraprevotella, Prevotella, and Bifodobacterium (Barengolts, et. al., 2018). The net result of this change is a disruption in short chain fatty acid production and bile acid balance which are crucial in reducing inflammation in the gut.

C. Psychostimulants

A considerable amount of research has been conducted on the effects of psychostimulants, particularly cocaine and methamphetamine, on the microbiota of rodents. Preclinical cocaine exposure in mice results in an increase in inflammation-inducing Proteobacteria, while rats exposed to methamphetamine exhibit a reduction in microbes which produce short chain fatty acids (SCFA), such as Ruminococcaceae, Lachnospiracea, and Butyricicoccus.

In studies of humans, methamphetamine users show a reduction in beneficial SCFA-producing Butyricicoccus and Fecalibacterium, and an increase in pathogenic Porphyromonas. Methamphetamine use also increases inflammatory responses in the brain and blocks proliferation of astrocytes in nervous tissue.

IV. Epilogue: So what can we do improve our gut health? On 15 April 2025, the Washington Post ran an article entitled “I’m a gastroenterologist. Here are 8 tips to improve your gut health”, written by Dr. Trisha Pasricha, who addressed this very question with 8 tips (https://www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2025/04/14/im-gastroenterologist-here-are-8-tips-improve-your-gut-health/):

- Don’t strain or linger on the toilet: Sitting or straining for long periods of time can compromise the supportive tissue in our anal canals, potentially leading to symptomatic hemorrhoids;

- Know what’s ‘normal’ for you: For some people, one bowel movement per day is ‘normal’, but for others, “anywhere from three bowel movements per week to three per day is within the range of ‘normal;’”

- Avoid taking drugs like ibuprofen: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs, can damage the gut lining. This includes ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin;

- Minimize your intake of sugary drinks and red meat: Eating a Mediterranean-style diet, which is rich in legumes, nuts, fruits and vegetables, can reduce the risk of colorectal cancer by around 18 percent;

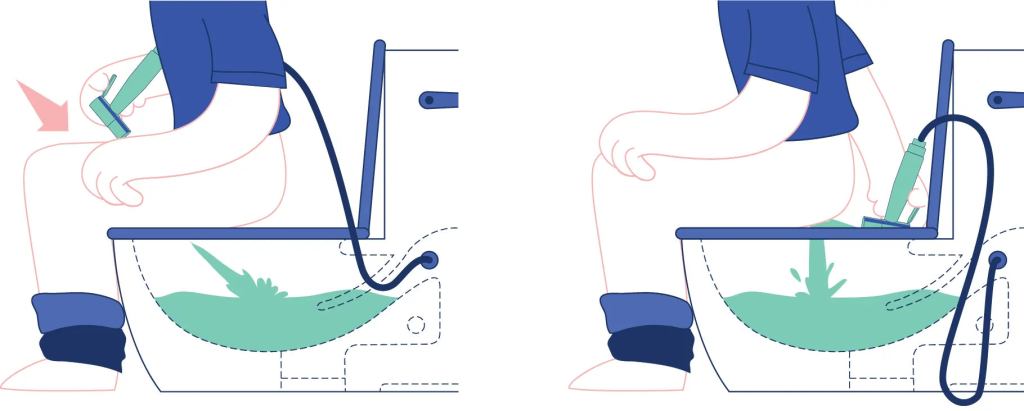

- Go on. Try a bidet: Bidets are gentle and hygienic, and are recommended for patients with loose stools, like in irritable bowel syndrome, who find that constant wiping makes their skin raw, and for anyone who might struggle with balance or coordination reaching back to wipe. It is highly recommended for women postpartum;

- Eat a fiber-rich diet: The more diverse your diet, the more diverse your microbiome, and the healthier you are;

- Worried about smelly gas? Try bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol): This medication has it been shown to neutralize more than 95 percent of sulfide gases in the gut and to reduce symptoms of flatulence, and it can also prevent traveler’s diarrhea;

- Think twice before cutting dairy entirely: About two-thirds of the world’s population gradually lose the ability to synthesize lactase, the enzyme which breaks down lactose in the small intestine. As a result, intact lactose will enter the small intestine and ferment, leading to the production of gas and bloating. Studies have found that most people with lactose intolerance can tolerate at least 12-15 grams of lactose in one sitting — the equivalent of about one cup of milk. This is important because dairy products are some of our main sources of calcium and vitamin D.

V. Wait, wait, you’ve never heard of a bidet and don’t know how they work? A bidet does not typically have a brush or scrubbing mechanism. Instead, it uses a stream of water to cleanse the area after using the toilet. The water pressure and angle can often be adjusted for comfort and effectiveness, but it relies on water rather than scrubbing action:

And here’s a picture:

P.S.:

Barengolts, E. et. al. (2018). Gut microbiota varies by opioid use, circulating leptin and oxytocin in African American men with diabetes and high burden of chronic disease. PLos One 13:e0194171. https://doi.org/10.1371.journal.pone.0194171

Clark, S.F.; Murphy, E.F.; O’Sullivan, O., et. al. (2014). Exercise and associated dietary extremes impact on gut microbial diversity. Gut 63(12):3636-3644.

Engen PA, Green SJ, Voigt RM, Forsyth CB, Keshavarzian A. (2015). The Gastrointestinal Microbiome: Alcohol Effects on the Composition of Intestinal Microbiota. Alcohol Res. 2015;37(2):223-36.

Hills, R.D. Jr. et. al. (2019). Gut microbiome. Profound implications for diet and disease. Nutrients. 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu 11071613.

Hugon, P.; Dufour, J.C.; Colson, P.; Fournier, P.E.; Sallah, K.; Raoult D. (2015). A comprehensive repertoire of prokaryotic species identified in human beings. Lancet Infect Dis 15(10):1211-1219.

Janhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Reddy, D.N. (2015). Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J Gastroenterol 2015 August 7; 21(29): 8787-8803. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i29.878.

Mutlu, E.; Keshavarzian, A.; Engen, P. (2009) Intestinal dysbiosis: A possible mechanism of alcohol-induced endotoxemia and alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 33(10): 1836-1846.

Odamaki, T.; Kato, K.; Sugahara, H.; Hashikura, N.; Takahashi, S.; Xiao, JZ. (2016). Age-related changes in gut microbiota composition from newborn to centenarian:

a cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiology (2016) 16:90

DOI 10.1186/s12866-016-0708-5.

Praagh, J.B.; Havenga, K. (2023). What is the Microbiome? A Description of a Social Network. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery 36:91-97.

Queipo-Ortuna, M.I.; Boto-Ordonez, M.; Murri, M.; et. al. (2012). Influence of red wine polyphenols and ethanol on the gut microbiota ecology and biochemical markers. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 95(6): 1324-1334.

Rimola, A. (1991). Infections in liver disease. In: Oxford Textbook of Clinical Hepatology. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press.

Rinnilella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A. Mele, M.C. (2019) What is the Health Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 7, 14; doi:10.3390/microorganisms7010014

Salavrakos, M.; Leclercq, S.; De Timary, P.; Dom, G. (2021). Microbiome and substances of abuse. Prog Neurophycopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 8:105:110113. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110113. Epub 2020 Sep 22.

Simpson, S.; Mclellan, R.; Wellmeyer, E.; Matalon, F.; George, O. (2021). Drugs and Bugs: The Gut-Brain Axis and Substance Use Disorders. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology 17:33-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-021-10022-7.