(Illustration from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/324948#psychological-health )

I. A few vignettes of what it was like then:

A. Woodstock as a point of reference – Summer, 1969

The Woodstock Music and Art Fair, also known as Woodstock, was a music festival held from August 15 to 18, 1969, on Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in Bethel, New York, about 40 miles southwest of the town of Woodstock. It is estimated that 460,000 people attended the event, at which 32 acts played. It is also estimated that “99% of the crowd was smoking marijuana” (https://www.ministryofcannabis.com/blog/2017/10/04/woodstock-1969-99-of-the-crowd-was-smoking-marijuana/).

The potency of the marijuana smoked at Woodstock was relatively limited. Marijuana tested at Woodstock in 1969 was usually Cannabis sativa at 1% THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) ( https://www.getsmartaboutdrugs.gov/news-statistics/2025/01/16/many-risks-cannabis-and-high-dose-thc.)

Wait, did someone say “Woodstock”? —

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HKdsRWhyH30&list=RDHKdsRWhyH30&start_radio=1

B. At the State University New York at Stony Brook, 1971

As students at the State University of New York at Stony Brook (now called Stony Brook University), my roommate and I would listen to the radio station of the University of Bridgeport (CT), which was just across the Long Island Sound.

One night, we heard the DJ say the following:

“We got what you want,

We got what you need,

Acapulco Gold is

BAD-ASS WEED!”

C. A vignette from graduate school – 1975

Following graduation from college and entering graduate school, I met a veteran who was a translator for the First Armored Division in Da Nang, Vietnam. He said that when they had incoming fire, the drunks were worthless, but those who were smoking cannabis could at least take their battle stations.

True, this vignette is not much of a baseline, but that vignette suggests that no matter how high people got when smoking weed, they could still perform certain functions with some reliability.

II. What it’s like now

The concentration of the principal active ingredient in cannabis, THC, has increased significantly over the past 50 years, as shown in the figure below, which appeared in https://www.newscientist.com/article/2396976-is-cannabis-today-really-much-more-potent-than-50-years-ago/ :

Now, most strains claim to be at least 20 to 30% THC by wait, and concentrated weed products designed for vaping can be labeled as up to 90% (Ferguson, 2024). Numerous people, especially teens, have experienced short- and long-term “marijuana-induced psychosis”, during which they may experience chronic vomiting and auditory hallucinations of talking birds.

The consequences are quite serious, given the fact that as the concentration of THC in cannabis has increased, there has been a concomitant increase in the number of states in the United States, and of countries, which are legalizing cannabis for both recreational and medical use.

For example, Arterberry, et. al. (2019) have shown that whereas individuals initiating cannabis at national average 4.9% delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol were at 1.88 times (p = .012) higher risk for cannabis use disorder symptom onset within one year, those individuals initiating cannabis at national average 12.3% delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol were at 4.85 times (p = .012) higher risk within one year.

III. Over time, cannabis use affects brain function, and not in a good way.

In 2025, Gowin, et. al., published a study in which they examined the association of lifetime history of heavy cannabis use and recent cannabis use with brain activation across a range of brain functions in a large sample of young adults

in the US.

Their study included 1003 adult participants with an average age of 28.7, of whom 88 participants (8.8%) were classified as heavy cannabis users, 179 (17.8%) as moderate users, and 736 (73.4%) as nonusers.

To assess the effects of cannabis, each participant underwent the following:

- Complete MRI scans

- Urine sampling to detect cannabis metabolites. Usually a positive test indicates cannabis use within the past 10 days. However, concentrations of 11-Nor-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid exceeding 50 ng/ml may indicate use during the prior month or even before that;

- Completion of the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA). The interview assessed total lifetime number of cannabis uses on a Likertrated scale (with response levels of never, 1-5, 6-10, 11-100, 101-999, and >1000). We categorized individuals as nonusers if they had used 10 or fewer times, as moderate users if they had used 11 to 999 times, and as heavy users if they had used 1000 or more times. The SSAGA also assessed a diagnosis of cannabis dependence (lifetime) (per DSM-IV criteria) and age at first cannabis use (never or <14, 15-17, 18-20, or >21 years);

- Completion demographic screening to indicate age, sex, race, income, and education;

- 7 tasks, designed o cover a broad range of behavioral processes. Tasks were chosen based on reliability of neural response and a well-characterized neurocognitive basis. The tasks examined neural response related to emotion, reward, motor function, working memory, language, relational or logical reasoning, and theory of mind or social information processing Neural response to the tasks has previously discriminated substance use history. For each task, we used the primary contrast, and we extracted activation levels from regions positively activated during the task (ie, regions in the brain engaged by the task, not regions that were deactivated by the task, such as nodes in the default mode network). Positive activation was defined as having significant activation (2-tailed P < .001), with most effect sizes (Cohen d) greater than 1.00 for the contrast (the task positive condition minus the control condition). The mean value of the activation levels across the listed regions for each task was used, so each participant had a single value representing the activation level for each task;

The results of their research revealed the following:

- Participant characteristics

- Heavy lifetime users were more likely to be male, to have lower income, and to have lower levels of education than nonusers;

- Heavy lifetime users were also more likely to have positive THC urine screens and a diagnosis of dependence relative to moderate users and nonusers;

- Heavy lifetime users also had higher scores for nicotine dependence severity and alcohol use relative to those with negative THC test results.

- Brain Activation Outcomes of Cannabis Use

- Heavy lifetime cannabis use was associated with lower brain activation only during the working memory task, and this association remained after excluding individuals with recent use

- Heavy lifetime cannabis use among participants was associated with lower activation to a working memory task even after removing individuals with a positive urine screen at the time of testing to control for recent use;

- Acute THC administration reduces brain activation in brain regions involved in working memory.

IV. There is now evidence of an increase in schizophrenia and psychosis as a consequence of the consumption of cannabis with increased concentrations of THC. Here’s the evidence from a study conducted by Myran et. al. (2025).

The steps leading to the legalizing of nonmedical cannabis in Canada were gradual. In 2001, cannabis was legal for a limited list of severe or chronic medical conditions, but was greatly expanded in 2014 for anyone with medical authorization from a physician indicating they would therapeutically benefit from cannabis. In December 2015, the federal government

committed to legalizing nonmedical cannabis, and this policy commitment led to large increases in illicit and gray market medical and nonmedical cannabis dispensaries and online vendors. Finally, legalization of nonmedical cannabis came into effect in October 2018, making Canada the first country in the world to allow commercial sale of nonmedical cannabis.

In early 2020, the market in Ontario began to commercialize with the introduction of new products with high THC content (concentrates, vapes, and edibles) along with the removal of

store restrictions. These policy changes, combined with robust health administrative data capturing all health system encounters for all residents of Ontario, provide a unique opportunity to understand the association of cannabis policy changes with the risk of schizophrenia. We examined how the

population-attributable risk fraction (PARF) for cannabis use disorder (CUD) associated with schizophrenia changed over time in Ontario in response to medical cannabis liberalization and nonmedical cannabis legalization with restrictions.

A total of 13,588,681 individuals with a mean age of 39 were included in the study over a 16-year period, of whom 50.1% were male. A total of 118,650 (0.9%) were diagnosed with Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD). During the time of the study, a total of 91,106 individuals (0.7%) developed schizophrenia, 80,523 of 13,470,031 (0.6%) in the general population without CUD vs 118,650 (8.9%) with CUD.

Therefore, in this population-based cohort study comprising 13 588 681 individuals, the population-attributable fraction of cannabis use disorder (PARF) associated with schizophrenia increased significantly from 3.7% in the prelegalization period to 10.3% during the postlegalization period. The following graph shows the progressive increase in incidence in schizophrenia and in psychosis with the concomitant changes in cannabis’ legal status in Canada.

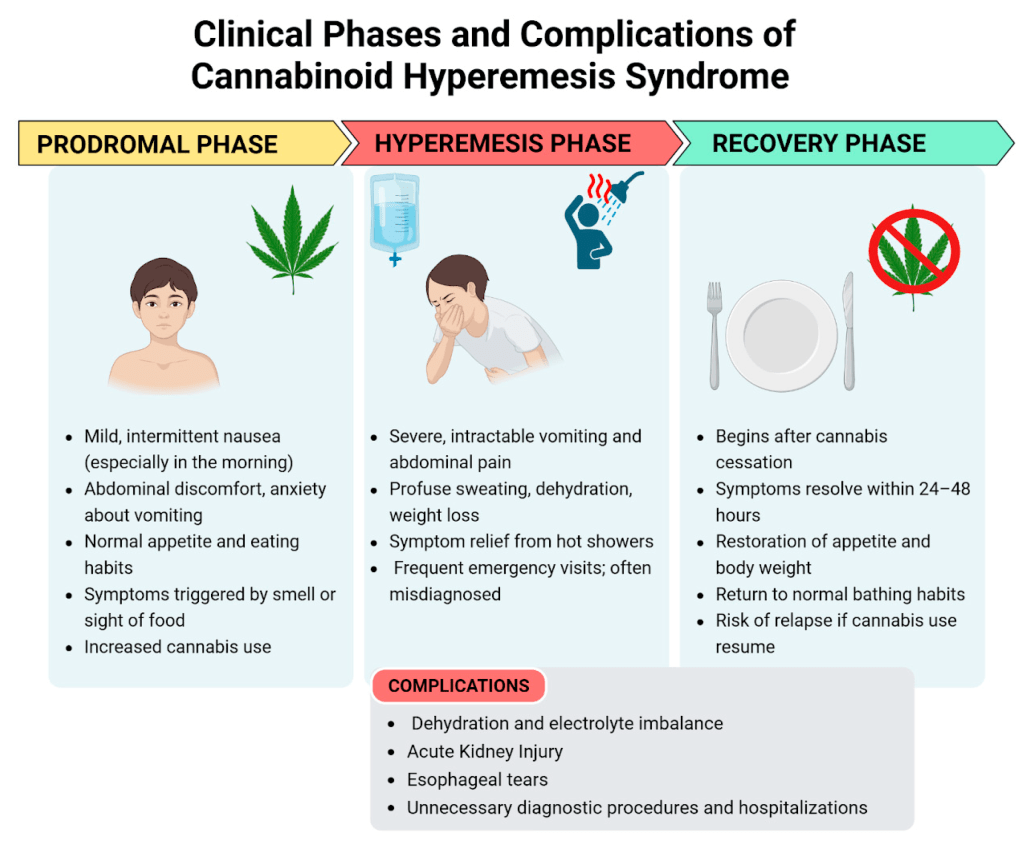

V. First described in 2004 in Australia, Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome is increasing in frequency (Allen, et. al., 2004).

Stacey Colino and Brian Kevin start their article, This strange syndrome is linked to regular cannabis use—and cases have doubled with a brief case history sketch of one person, Sierra Callaham, who developed periodic monthlong bouts with “daily abdominal pain, nausea, and cyclical vomiting.” When she admitted to an emergency room physician that she used cannabis daily, the physician gave her a provisional diagnosis: cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS), sometimes simply called weed sickness (Colino and Kevin, 2025).

The following infographic, from the Cleveland Clinic, shows the symptoms associated with this syndrome:

The two factors that are associated with the increased incidence of this syndrome are the increased potency of cannabis products and the increased availability of these products due to their legalization for both medical and recreational uses.

Regarding the increased potency of cannabis products, Colino and Kevin (2025) state the following: “Thirty years ago, samples seized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration averaged 4 percent THC content by weight. As of 2022, that average is about 16 percent; the oil in vape cartridges like what Callaham was using can reach as high as 85 percent.”

And what about the increased availability of cannabis products? Again, from Colino and Kevin (2025): “In one characteristic study, published in 2022 in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, researchers compared admissions for CHS at a large Massachusetts hospital between 2012 and 2020, noting a significant uptick after cannabis was legalized in the state in late 2016.”

Oddly enough, people with CHS often spend a lot of time in the shower. Apparently, people with this syndrome get temporary relief of the symptoms of CHS by bathing in hot water. Perhaps this means that the area hypothalamus, the part of the brain that helps regulate body temperature, is involved in CHS.

VI. What has been the incentive to increase the concentration of THC in marijuana?

The “mids”, i.e. middle-tier weed, and reggies (regular weed) are no longer the industry’s top customers. Ferguson (2024) reports that research shows that people who report smoking more than 25 times a month make up about a third of marijuana users but account for about 2/3 of all marijuana consumption. These stoners develop a high tolerance, and it is for them that the industry is producing these high-potency strains.

Since US government regulations still consider marijuana as an illegal drug, there is no federal regulation or safety-testing of marijuana products at the national level. Even if marijuana was rescheduled marijuana to a legal Schedule 3 status, it will allow the expansion of medical-marijuana research and access, but it still won’t affect the recreational market. The solution very well may be to deschedule marijuana, which would allow the federal government to allow the establishment and enforcement of health and safety regulations for recreational use as well.

VII. Price list for weed from the Ontario Cannabis Store (prices are in Canadian dollars)

| Name of strain | Type | Starting price per gram |

| Purple poison | Hybrid | $3.57 |

| Kush Dreams | Indica Dominant | $3.57 |

| Buddies | Hybrid | $3.57 |

| Grower’s Choice Sativa | Sativa Dominant | $3.57 |

| Tropical Hazy Daze | Sativa Dominant | $3.57 |

| Sweet Island Skunk | Sativa Dominant | $3.57 |

| Blueberry | Indica Dominant | $3.57 |

| Sour Kush | Hybrid | $3.57 |

| BC God Bud | Indica Dominant | $3.71 |

| Sweet Notes | Hybrid | $3.72 |

| Peach Tree | Sativa Dominant | $3.87 |

| Lemonatti | Sativa Dominant | $3.87 |

P.S.:

For me, this is the quintessential song that describes what Woodstock was like:

P.P.S.: And then there are these more recent gems:

Ahrens, J.; Ford, S.D.; Schaefer, B.; Reese, D.; Khan, A.R.; Tibbo, P.; Rabin, R.; Cassidy, C.M.; Palaniyappan, L. (2025). Convergence of Cannabis and Psychosis on the Dopamine System. JAMA Psychiatry. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2025.0432

Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, et al. (2004). Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Gut 2004;53:1566-1570.

Arterberry, B.J.; Padovano, H.T.; Foster, K.T.; Zucker, R.A.; Hicks, B.M. (2019). Higher average potency across the United States is associated with progression to first cannabis use disorder symptom. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 195: 186-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.11.012 .

Colino, S.; Kevin, B. (2025). This strange syndrome is linked to regular cannabis use—and cases have doubled. National Geographic – https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/chs-cannabis-marijuana-risks .

Ferguson, M. (2024). Marijuana Is Too Strong Now. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/08/high-potency-marijuana-regulation/679639/

Gowin, J.L.; Ellingson, J.M.; Hollis, C. Karoly; Manza, P.; Ross, J.M.; Sloan, M.E.; Tanabe, J.L.; Volkow, N.D. (2025). Brain Function Outcomes of Recent and Lifetime Cannabis Use. JAMA Network Open. 2025;8(1):e2457069. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.57069

Myran, D.T.; Pugliese, M.; Harrison, L.D.; Solmi, M.; Anderson, K.K.; Fiedorowicz, J.G.; Finkelstein, Y.; Manuel, D.; Taljarrd, M.; Webber, C.; Tanuseputro, P. (2025). Changes in Incident Schizophrenia Diagnoses Associated With Cannabis Use Disorder After Cannabis Legalization. JAMA Network Open. 2025;8(2):e2457868. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.57868 .

Testai, F.D.; Gorelick, P.B.; Aparicio, H.J.; Filbey, F.M.; Gonzalez, R.; Gottesman, R.F.; Melis, M.; Piano, M.R.; Rubino, T.; Song, S.Y. (2022). Use of Marijuana: Effect on Brain Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2022;53:e176–e187. DOI: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000396.