BLUF (Bottom Line, Up Front): Pick your poison wisely

When I was in college (late 60’s to early 70’s) the prevailing opinion was that cannabis was no worse than alcohol. If you think about it, that’s not much of a glowing recommendation on behalf of cannabis.

However, I wish to offer two vignettes about the difference between getting high on weed as opposed to alcohol:

Vignette 1: As a graduate student in zoology, 1972-1978, I befriended a veteran who was a translator for the First Armored Division in Danang during the Vietnam war. He said that when there was incoming fire, “those soldiers who were high on marijuana were still able to man their battle stations, but the ones who were drunk were absolutely worthless.” (Please bear in mind that he served in the late ’60s, when the THC concentration was only ~2%.)

Vignette 2: I described this conversation in a previous blog that I had with a police officer, about twenty-five years later, at a time when a variety of states, including Colorado and California, were just starting to pass legislation legalizing the use of cannabis for medical or recreational use. I asked him whether he thought that the legalization of marijuana in Tennessee would be a good idea. He was extremely adamant in his answer, pounding his fist on the handlebar of the stationary bicycle, and said, “ABSOLUTELY! It should be legal for BOTH medicinal AND recreational purposes, and THE SOONER, THE BETTER!!” I was taken aback by the intensity of his answer, so I asked him, “How so?” He replied thus: “When was the last time I had to break up a fight between two drunks who were having an argument? (Looks at his watch.) Like, at 3 a.m. this morning!…and when was the last time I had to break up a fight between two potheads? Like, NEVER!!”

So there you have it.

I. Cannabis

Times, and the potency of cannabis, have changed. The legalization of cannabis for medical and recreational purposes has allowed scientists to see conditions and medical issues that are problematic.

A. Psychosis and hallucinations

In a previous blogpost, #60, I described the progressive increase of psychoactive compounds in cannabis, and this has led to an increased incidence in schizophrenia and psychosis. During these episodes of psychosis, numerous people, especially teens, have admitted that they experience chronic vomiting and auditory hallucinations of talking birds.

B. The issue of pain management

Despite plenty of testimonies from people who believe that the intensity of pain that they experience is reduced when they use cannabis, research on the subject indicates a lack of sufficient evidence to endorse the general use of cannabinoids for the treatment of pain.

Actually, recent news reports indicate that Mr. Nelson has decided to discontinue smoking cannabis, but “he continues to use pot.” See https://apnews.com/article/music-country-music-us-news-marijuana-celebrities-972200799819586a2f0ddc9976fa2f0e .

In 2021, the International Association for the Study of Pain issued a position statement on the use of cannabinoids for the treatment of pain, and it does endorse the general use of cannabinoids for this purpose:

” INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF PAIN COMPLETES COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW OF RESEARCH ON THE USE OF CANNABINOIDS TO TREAT PAIN AND FINDS THAT THERE IS A LACK OF SUFFICIENT EVIDENCE TO ENDORSE THE GENERAL USE OF CANNABINOIDS FOR THE TREATMENT OF PAIN” (IASP, 2021).

Rather than closing the door on the topic, they call for more rigorous and robust research to better understand potential benefits, so their position may change in the future.

Nonetheless, the therapeutic effect experienced by some users may be explained by the placebo effect, in which the reduction in pain is due to peoples’ expectations that it would help. Gedin (et. al., 2022) undertook a meta-analysis of 20 different studies, involving 1459 individuals, and found that 67% of the relief from pain reported by people treated with cannabinoids was also seen among those who received a placebo.

Here is how they reported the results in their Abstract:

Results: Twenty studies, including 1459 individuals (mean [SD] age, 51 [7] years; age range, 33-62 years; 815 female [56%]), were included. Pain intensity was associated with a significant reduction in response to placebo, with a moderate to large effect size (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.64 [0.13]; P < .001). Trials with low risk of bias had greater placebo responses (q1 = 5.47; I2 = 87.08; P = .02). The amount of media attention and dissemination linked to each trial was proportionally high, with a strong positive bias, but was not associated with the clinical outcomes.

C. Other concerns

- Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS) is a condition that was first described in 2004, and is characterized by recurring episodes of nausea, vomiting, and severe abdominal pain (Colino, 2014);

- People who use the drug regularly have a higher risk for heart attack, stroke, and other heart disease. In a large-scale study involving 27 American states and 2 territories, Jeffers, et. al. (2024) found that people who use the drug regularly have a higher risk for heart attack, stroke, and other heart disease. In fact, heart attack rates rose 25 percent while stroke increased 42 percent among individuals who regularly use cannabis.

II. Alcohol

Let us agree that imbibing excessive amounts alcohol will compromise your cognitive abilities, manners, and interpersonal relationships. BTW, this particular song is deliciously naughty, but you have to admit that a wife’s gotta do what’s she gotta do:

Seven Drunken Nights – YouTube Music

While attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, a friend of mine related a story in which the featured speaker said “that by becoming an alcoholic, I started the installment plan for killing myself.”

The statement regarding the installment plan is stark, but it is quite accurate considering the long-term effects of alcohol on all organ systems in the human body:

(Above figure from Alcohol’s Effects on Health, https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohols-effects-body )

I would like to take a closer look at steatosis (fatty liver), which is reversible, and cirrhosis, which is not.

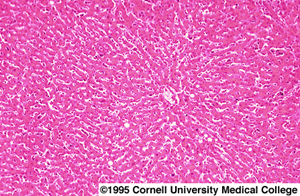

As mentioned in my welcome page, I taught a course on the biology of addiction, in which I went into exquisite detail about alcohol and other psychoactive drugs and their short- and long-term effects on the body. In the chapter dealing with alcohol, I included images of photomicrographs taken of a healthy liver, a fatty liver, and a liver showing cirrhosis. I used these images in the textbook I wrote, Men, Women, and Their Addictions: A Biological Approach (2003).

The tissue inside a healthy liver is divided into blocks called sinusoids, in which blood vessels course between the sinusoids to allow the rapid movement of blood to the liver for delivery of digested foods which will be ultimately distributed to the rest of the body, and of drug compounds, each of which will undergo a chemical detoxification process. To me, a photomicrograph of a healthy liver resembles an aerial view of a well-planned city subdivision, in which the blocks (sinosoids) are clearly separated by streets (blood vessels).

This configuration is clearly disrupted in a fatty liver, which has been damaged by the highly reactive forms of oxygen which are generated during the breakdown of ethanol into carbon dioxide and water. A fatty liver is shown below:

Here, the large clear blobs indicate deposits of fat.

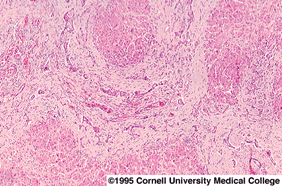

If the individual continues to drink, the cells of the liver will die, and the tissues which formed the sinusoids will appear crushed, with no blood vessels coursing between them, and this is indicative of cirrhosis:

Even before we get to these potentially disastrous and fatal consequences, we are all familiar with the short-term effects of alcohol, which can also be potentially disastrous and fatal:

(The above figure is from New Leaf Detox and Treatment, https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohols-effects-body)

Colino, S. (2014). This strange syndrome is linked to regular cannabis use—and cases have doubled. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/chs-cannabis-marijuana-risks

Gedin, F.; Blome, S.; Ponten, M.; Lalouni, M.; Fust, J.; Raquette, A.; Lundquist, V.V.; Thompson, W.H.: Jensen, K. (2022). Placebo Response and Media Attention in Randomized Clinical Trials Assessing Cannabis-Based Therapies for Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open 2022;5;(11):e2243848. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.43848

International Association for the Study of Pain (2021). https://www.iasp-pain.org/publications/iasp-news/iasp-position-statement-on-the-use-of-cannabinoids-to-treat-pain/

Jeffers, A.M.; Glantz, S.; Byers, A.L.; Keyhani, S. (2024). Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults. Journal of the American Heart Association, Volume 13, Number 5, https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.030178