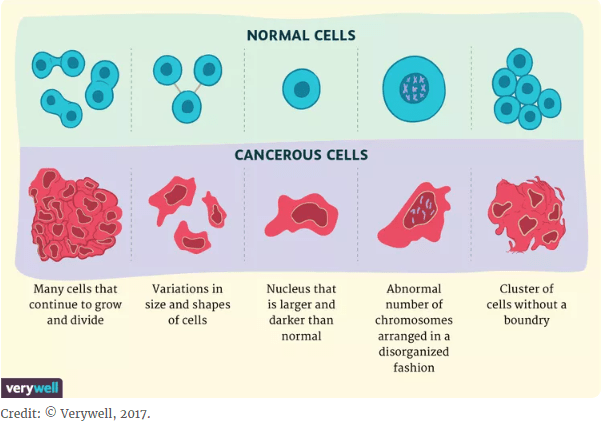

The website https://www.verywellhealth.com/cancer-cells-vs-normal-cells-2248794 is a good starting point to compare normal cells from cancerous cells. First, their appearances are different:

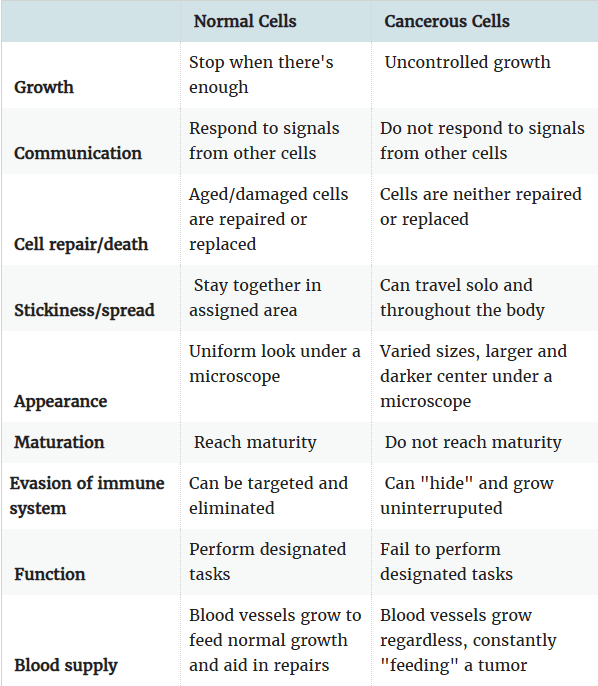

Furthermore, cancerous cells differ from normal cells in their behavior:

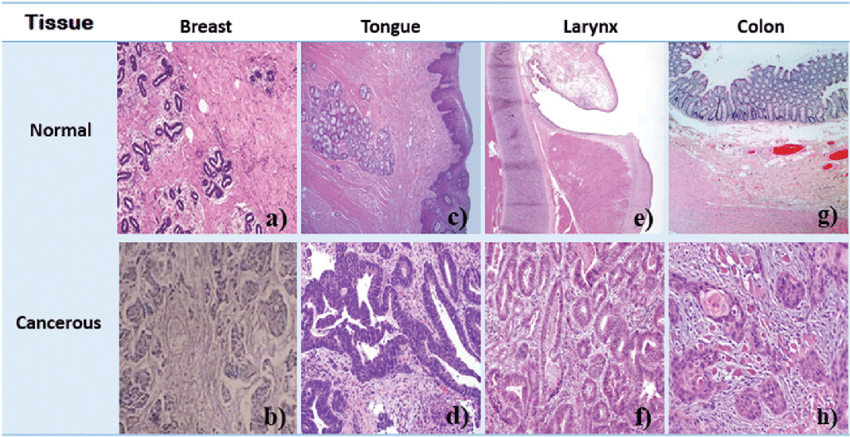

The net result of these differences is that a pathologist can distinguish healthy tissue from cancerous tissue, as in the following examples:

Above figure from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Histological-images-of-normal-and-cancerous-a-b-breast-c-d-tongue-e-f_fig2_320463567, uploaded by M. R. Mohebbifar.

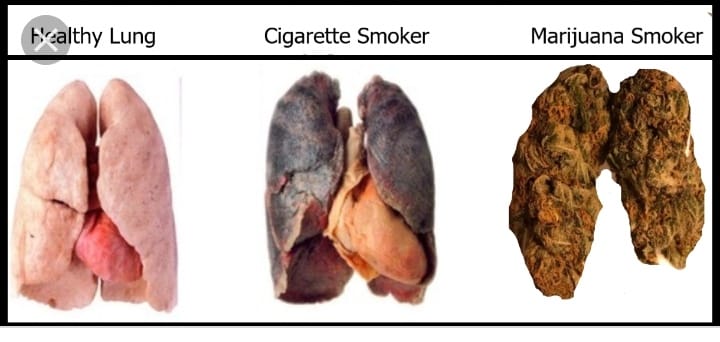

And the gross anatomy of the lungs from a habitual marijuana smoker is about as ugly as those of a tobacco smoker:

The consequences of smoking tobacco cigarettes are well known, and include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchogenic carcinoma, and an increased predisposition to lower respiratory infection (Tashkin, 2005).

In 2023, Reece, et. al. published a report on the incidence and types of cancer found among individuals who consume cannabis. They found that cancer rates in high-cannabis-use countries were significantly higher than elsewhere. Furthermore, they found that eighteen of forty-one cancers were significantly associated with cannabis exposure, including the following:

- Hepatocellular cancer

- Laryngeal cancer

- Lung cancer

- Breast cancer

- Cancers of the thyroid and liver

- non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Pancreatic cancer

- Testicular and cervical cancers

- Anal cancer

- Cancer of the vulva

- Kaposi’s sarcoma

To what can we attribute this association between cannabis smoke and various forms of cancer? First, cannabis smoke contains all of the tars and other carcinogens found in tobacco smoke. Second, cannabis dramatically increases mitotic and meiotic division error rates in both sperm and oocytes. Third, cannabis, THC, cannabidiol, cannabinol, and cannabichromene induce single- and double-stranded chromosomal breaks, which are a major cause of genotoxicity and mutagenicity (Reece, et. al., 2023).

The transition of a line of normal cells to cancerous cells often takes time, measured in decades, during which there are multiple mutations which accumulate to the point that the normal “brakes” in cellular division disintegrate. For example, testicular cancer is assumed to develop over 33 years, based on the activation of genotoxic changes caused by the hormonal surge of puberty. However, if we accept the median age of cannabis exposure of 20 years, then it follows that testicular cancer will develop following cannabis exposure over only 13 years. This means that exposure to cannabis causes a significant acceleration of oncogenic incubation.

It stands to reason that cannabis could be a cause of various types of cancer, for a number of reasons:

- It is smoked without a filter;

- People generally inhale the smoke more deeply than with tobacco cigarettes;

- As people inhale the smoke, they keep it in their lungs for a longer period of time to get the desired transfer of THC into their bodies;

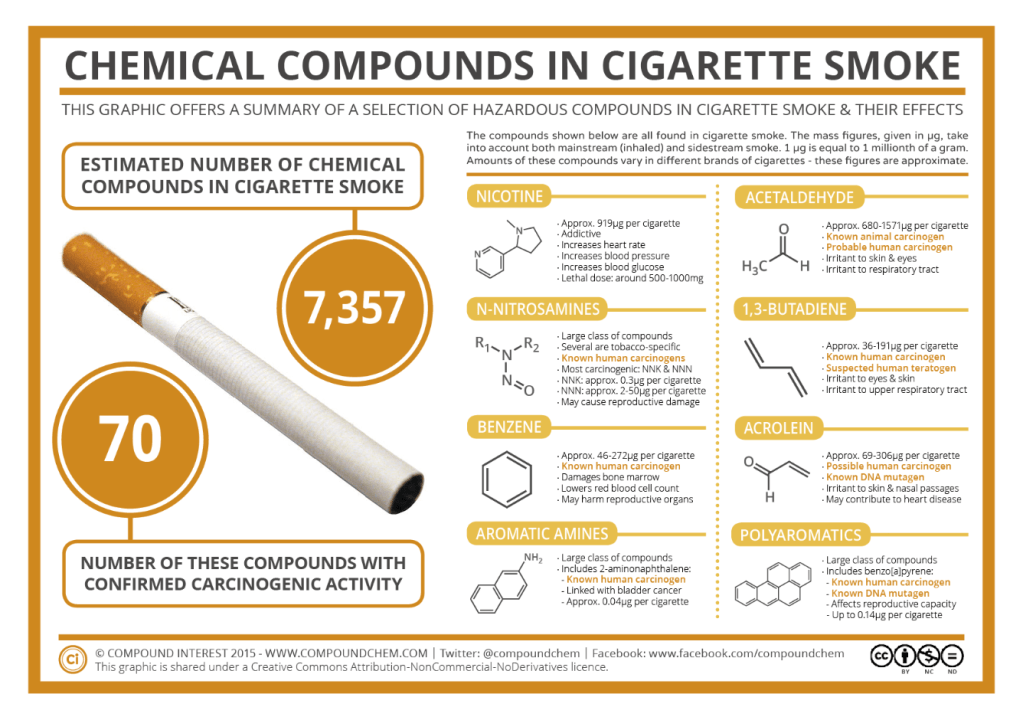

- The smoke generated from a marijuana joint contains the same carcinogenic compounds as that generated from a tobacco cigarette (Hashibe, et. al., 2005):

- Vinyl chlorides;

- Phenols;

- Nitrosamines;

- Reactive oxygen species; and

- Various polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

- Benzene

- Acroleine

- Benzo(a)pyrene

- Cannabis may exert immunosuppressive effects, particularly through modulation of T-cell function, which is that branch of our immune system responsible for cancer immunosurveillance (Cuomo, R.E., 2025a);

- When cannabis use disorder (CUD) induces depression and anxiety, it can negatively influence cancer treatment adherence and prognosis;

- Patients with substance use disorders, including CUD, are at higher risk for delayed diagnoses, suboptimal medical engagement, and lower adherence to recommended oncologic treatments (Sarfati, et. al., 2016).

The following infographic, extracted from https://www.compoundchem.com/2014/05/01/the-chemicals-in-cigarette-smoke-their-effects/, summarizes the list of carcinogenic compounds found in tobacco cigarette smoke, most of which are also found in cannabis smoke:

At the same time, however, the frequencies that average tobacco cigarettes and marijuana joints are consumed are quite different. For example, Graves, et. al. (2020) report that in Canada, the average smoker of tobacco will consume 13.7 cigarettes per day, corresponding to ~390 cigarettes per month, while 55% of marijuana users report using it three times or less per month, with only 19% of users reporting using it daily.

As we will see below, there is a difficulty in defining the contribution of cannabis to cancer as opposed to tobacco, and that is that in most studies, both individuals with cancer AND their controls smoke BOTH tobacco and cannabis, so researchers require statistical tools to parse out the contribution of each to the incidence of the cancer under study.

The contribution of cannabis to various types of cancer

A. Pancreatitis and Pancreatic cancer

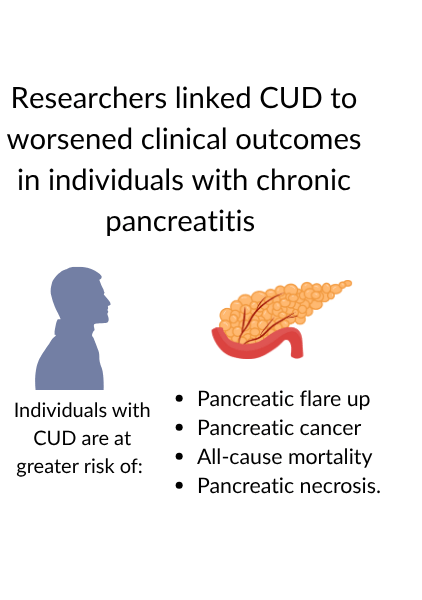

Earlier this year, Muhammad Hassaan Arif Maan delivered a paper at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025, who showed that “overuse of cannabis was linked to a heightened risk of acute pancreatitis flare, pancreatic cancer, and all-cause mortality compared with non-cannabis users ( https://www.hcplive.com/view/cannabis-use-dependence-linked-worse-clinical-outcomes-chronic-pancreatitis .

This study included 9062 patients in the cannabis use cohort, and an equal number in comparison cohort. The cannabis use cohort showed a significantly greater risk for the following:

- acute pancreatitis flare

- Pancreatic cancer

- All-cause mortality

- Pancreatic necrosis (no cases found in the control group)

B. Colon cancer

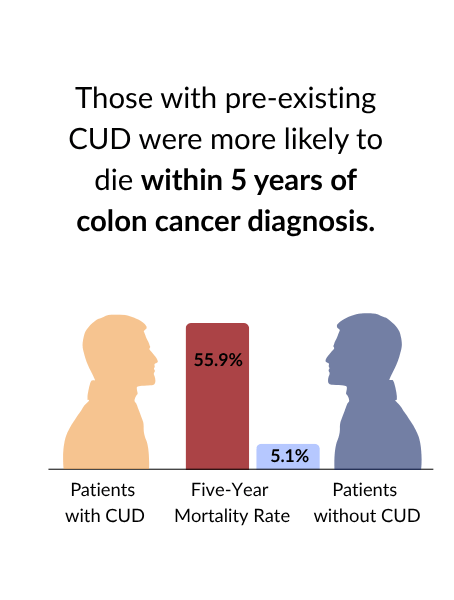

Cuomo (2025) examined data from the University of California Health Data Warehouse (UCHDW) to determine the impact of cannabis use disorder on mortality among patients with colon cancer. Where available, disease severity was captured via Tumor, Node, Metastasis (TNM) staging and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels, a biomarker associated with colon cancer progression. Metastatic stage was available for 95% of patients, while T and N stages were available for 53% and 55%, respectively.

A total of 1088 patients were surveyed, of whom 34 (3.1%) had CUD.

The difference in mortality is striking. The following Table is adapted from Table 1 of Cuomo (2025):

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with primary colon cancer (N=1088) included in the analytic cohort.

| Characteristic | Value |

| Total patients | 1088 |

| Patients with CUD, n (%) | 34 (3.1%) |

| Mean age at cancer diagnosis | 59.17 years |

| Female | 487 (44.8%) |

| Mean time from CUD diagnosis to cancer diagnosis | 135 days (before cancer) |

| Mortality within 5 years, n (%) | 70 (6.4%) |

| Mortality among CUD patients, n (%) | 19 (55.9%) |

| Mortality among non-CUD patients, n (%) | 51 (5.1%) |

C. Oral cancer

The same Raphael Cuomo, mentioned earlier in his study of the possible association between cannabis smoke and colon cancer, also conducted a study showing a relationship between Cannabis Use Disorder, CUD, and a five-year risk of oral (lip or tongue) cancer (Cuomo, 2025b).

This study included 45,129 patients whose clinical records were extracted from the University of California Health Data Warehouse. Of those eligible patients, 929 (2.1%) developed CUD. Oral cancer incidence was 0.4% in the CUD group and 0.23% in non-CUD patients. Those patients who developed CUD after drug use screening had, therefore, more than three times the odds of developing oral cancer within five years compared to patients who remained CUD-free. This association persisted after adjusting for age, sex, smoking status, and body mass index, supporting a robust relationship between CUD and oral cancer risk. Granted, the likelihood of developing oral cancer was low in both the CUD and non-CUD groups.

D. Lung cancer

Let’s admit the obvious: smoking cannabis is not good for your health. Multiple case reports show a relationship of cannabis smoking to numerous respiratory conditions, including the following (Kaplan, 2021):

- Aspergillosis

- Hemoptysis

- Emphysema and secondary pneumothorax;

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, eosinophilic pneumonitis,

- ARDS (Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- Vanishing lung syndrome.

Since many people who smoke cannabis also smoke tobacco, it is important to examine and perhaps distinguish the effects of each type of smoke on lung function before we look at the possible relationship between cannabis smoke and lung cancer:

- Although THC induces bronchodilation, which may be perceived as a good thing, the long-term consequences include airway inflammation, edema, and mucus hypersecretion. In a study comparing marijuana smokers (MS), marijuana and tobacco smokers (MTS), tobacco smokers (TS) and non-smokers (NS), Tashkin (2005) found the following:

- 18-19% of MS reported chronic cough and sputum production compared to 2-5% of NS;

- 24% of MS experienced on >= 21 days a year compared to 7% of NS;

- 13% of MS but only 2% of NS had >=2 episodes of acute bronchitis within the preceding 3 years;

- TS and MTS had a slightly higher prevalence than MS of similar symptoms.

- Lung function in both marijuana and tobacco smokers worsened over time, but the patterns were different

- The annual rate of change in forced expired volume in 1 second (FEV1) was not significantly different from that of NS. However, TS exhibited significant decrements compared to control NS in tests of small airways function cross-sectionally, as well as a significantly greater annual rate of decline in FEV1 than NS. This finding suggests that heavy, habitual smoking of marijuana, in the absence of tobacco, does NOT produce the early or progressive physiologic changes that precede the clinical development of COPD;

- In two different studies, one in the US and the other in New Zealand, marijuana use resulted in mild airflow obstruction, and we will look at specific results below;

- Both marijuana and tobacco smoke induce significant histological damage to the tracheobronchial mucosa. Erythema, edema, secretions, submucosal edema, and hyperplasia of the mucus-secreting goblet cells can be observed;

- The number and characteristics of alveolar macrophages, those cells which serve a critical role in host defense against infection, are altered. Among MS, TS, and MTS, there are 2-4 times as many alveolar macrophages recovered in a bronchial lavage than among NS, indicating an additive effect of marijuana and tobacco. Alveolar macrophages from both AM and TS revealed large irregular-shaped cytoplasmic inclusions, probably consisting of particles from tar;

- The bactericidal capabilities and phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages was impaired among MS, but not TS. This is probably due to inhibitory effect of THC on the ability of alveolar macrophages to produce nitric oxide, a crucial element in their ability to kill bacteria;

- Bronchial biopsies from heavy, habitual smokers show epithelial hyperplasia (an abnormal or unusual increase in cells composing a tissue), metaplasia (abnormal replacement of cells of one type by cells of another), and nuclear atypia (the abnormal appearance of a cell’s nucleus when viewed under a microscope) , i.e., changes that are observed in the development of bronchogenic carcinoma in tobacco smokers.

So now, we can look at some studies which verify that cannabis contributes to lung cancer. In order to compare the effects of type of smoke, researchers use two standardized measures. The first, joint-years, is defined as a joint per day for an entire year. The second, pack-years, is defined as 20 cigarettes per day for an entire year. These two measures account for daily consumption and for duration of usage.

- In 2008, Aldington, et. al. published a case-control study of lung cancer in adults <=55 years of age. Interviewer-administered questionnaires were used to assess possible risk factors, including cannabis use. The relative risk of lung cancer with cannabis smoking was estimated by logistic regression. They found that the risk of lung cancer increased for each joint-year of cannabis smoking and 7% for each pack-year of cigarette smoking, after adjustment for confounding variables including cannabis smoking;

- Also, in 2008, Berthiller, et. al. published a hospital based case-control studies in Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria, and pooled their data into one analysis. Ninety-six percent of the cases and 76.8% of the controls were tobacco smokers and 15.3% of the cases and 5% of the controls were ever cannabis smokers. All cannabis smokers were also tobacco smokers. Adjusting for country, age, tobacco smoking and occupational exposure, the odds ratio (OR) for lung cancer was 2.4 for ever cannabis smoking. They found that the risk of lung cancer increased with increasing joint-years, but not with increasing dose or cannabis smoking.

By the way, Kaplan (2021) disagrees with these findings that I mention above, because of small sample sizes. His opinion is that while cannabis smoke does damage the respiratory system, the convincing evidence that it causes lung cancer is lacking.

E. Head and neck cancer

Gallagher, et. al. (2025) conducted a study to determine whether

cannabis use is associated with head and neck cancer (HNC). Their study involved accessing a database that included 20 years of data (through April 2024) from 64 health care organizations, and included 116,076 individuals (51,646 women [44.5%]) with a mean (SD) age of 46.4 (16.8) years in the cannabis-related disorder cohort and 3 985 286 individuals (2 173 684 women [54.5%]) with a mean (SD) age of 60.8 (20.6) years in the non–cannabis-related disorder cohort. They found that the rate of new HNC diagnosis in all sites was higher in the

cannabis-related disorder cohort. Those with

cannabis-related disorder had a higher risk of oral oropharyngeal, and laryngeal cancer. Results were consistent when stratifying by older and younger age group.

Aldington, S.; Harwood, M.; Cox, B.; Weatherell, M.; Beckert, L.; Hansell, A.; Pritchard, A.; Robinson, G.; Beasley, R. on behalf of the Cannabis and Respiratory Disease Research Group. (2008). Cannabis use and risk of lung cancer: a case-control study. Eur Respir J. 31:280-286. DOI: 10.1183/09031936.00065707.

Berthiller, J.; Straif, K.; Boniol, M.; Voirin, N.; Benhaim-Luzon, V.; Ben Ayoub W.; Dari, Im; Laouamri, S.; Hamdi-Cherif, M.; Bartal, M.; Ben Ayed, F.; Sasco, A.J. (2008). Cannabis Smoking and Risk of Lung Cancer in Men: A Pooled Analysis of Three Studies in Maghreb. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 12:1398-1403.

Cuomo, R.E. (2025a). Cannabis use disorder and mortality among patients with colon cancer. Annals of Epidemiology 106(2025):8-10. https:/./doi.org/10.1016/j.annepide.2025.04.012.

Cuomo, R.E. (2025b). Cannabis use disorder and five-year risk of oral cancer in a multicenter clinical cohort. Preventive Medicine Reports 103185. https://doi.org/10.1016.j.medr.2025.103185.

Gallagher, T.J.; Chung, R.S.; Lin, M.E.; Kim, I.; Kokot, N.C. (2024). Cannabis Use and Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024;150(12):1068-1075. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2024.2419

Graves, B.M.; Johnson, T.J.; Nishida, R.T.; Dias, R.P.; Savareear, B.; Harynuk, J.J.; Kazemimanesh, M.; Olfert, J.S.; Boies, A.M. (2020). Comprehensive characterization of mainstream marijuana and tobacco smoke. Scientific Reports 10:7160. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63120-6.

Hashibe, M.; Straif, K.; Tashkin, D.P.; Morgenstern, H.; Greenland, S.; Zhang, Z-F. (2005). Epidemiologic review of marijuana use and cancer risk. Alcohol 35(3):265-275.

Kaplan, A.G. (2021). Cannabis and Lung Health: Does the Bad Outweigh the Good? Pulm. Ther. 7:395-408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41030-021-00171-8.

Reece, A.S.; Bennett, K.; Hulse, G.K. (2023). Cannabis- and Substance-Related Carcinogenesis in Europe: A Lagged CAusal Inferential Panel Regression Study. J. Xenobiotics 13:323-385. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox13030024.

Sarfati, D.; Koczwara, B.; Jackson, C. (2016). The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatment. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66(4):337-350.

Tashkin, D.P. (2005). Smoked Marijuana as a Cause of Lung Injury. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 63(2):93-100.