Dry January is a program, originating in the United Kingdom, in which people commit to 31 days of abstinence from drinking any alcoholic beverage. Here is an excerpt of how it started:

Dry January® started in 2013 with 4,000 people. Now in it’s 11th year it’s come a long way since then, with over 175,000 taking part in 2023.

2011

In 2011 Emily Robinson signs up for her first half marathon. It’s due to take place in February. She doesn’t like running much so to make the training easier, she decides to give up booze in January. She loses weight, sleeps better and feels like she has more energy to do the run.

But something else happens…

Everyone wants to talk to her about what it’s like to give up drinking for a bit.

2012

In January 2012, Emily joins Alcohol Change UK. She’s decided to give up drinking again this January. Now that she works for Alcohol Change UK, even more people want to talk to her about giving up drinking for a month. This sparks off lots of different conversations about the benefits of having a break from drinking – especially after Christmas. Watch Emily talk about Dry January®’s origins in this video.

That got us thinking. If we got more people having a break from booze in January, could we get more people thinking about their drinking? And would they drink less after their month off because actually they enjoyed the break so much?

The idea for the Dry January® campaign was born.

2013

The first Dry January®. We kicked off the first year of the campaign with Alastair Campbell talking about his past drinking, and columnist Peter Oborne trying out the month off booze.

A debate about the usefulness of giving up alcohol for a month kicks off. Can a month alcohol-free really make a difference long-term?

We decided to work with alcohol behaviour change expert Dr Richard de Visser from the University of Sussex. He volunteered for free to survey the people taking part in Dry January® to see what effects taking part in the campaign has on them.

De Visser found that six months after the campaign has finished, seven out of ten people have continued to drink less riskily than before. Almost a quarter of the people who were drinking at “harmful” levels before the campaign are now in the low risk category. (Emphasis mine.)

You can get more information at https://alcoholchange.org.uk/help-and-support/managing-your-drinking/dry-january

In 2023, Ms. Robinson was interviewed about the creation of this movement: https://alcoholchange.org.uk/help-and-support/managing-your-drinking/dry-january/about-dry-january/dry-january-10-year-anniversary

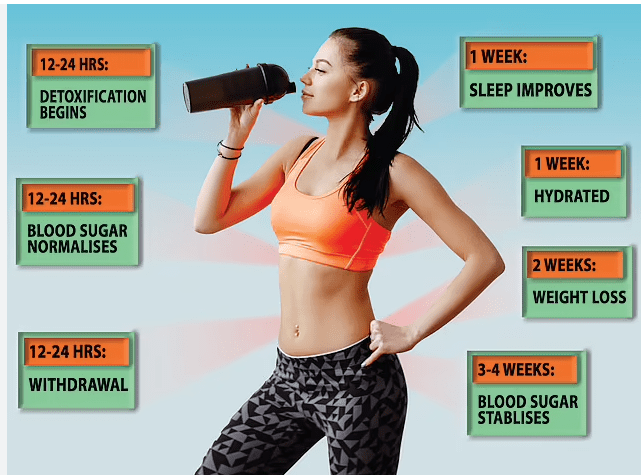

And in Australia, it’s dry July: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-9735127/Dry-July-one-month-without-alcohol-transform-health-mental-wellbeing.html

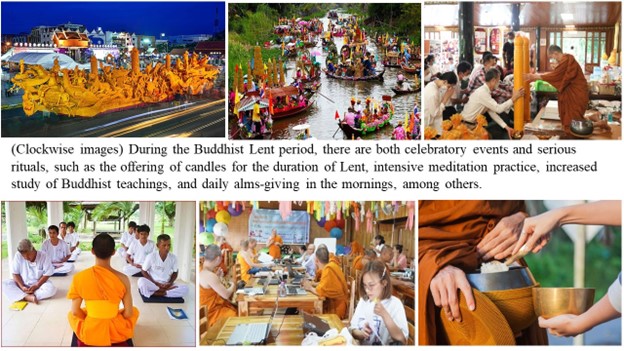

In Thailand, their temporary drinking abstinence campaign, the Buddhist Lent Abstinence Campaign, has been organized annually since 2003, and encourages Thai people to abstain from drinking for three months during the Buddhist Lent period, which coincides with the monsoon season in Southeast Asia (around July – October) (Saengow, 2019).

Studies indicate that people who participate in these short-term abstinence programs decrease their drinking frequency, intoxication episodes, and drinking amount per drinking day in the sixth month after the campaign.

The campaign in Thailand, the Buddhist Lent Abstinence Campaign, utilizes the fact that most Thais (93.6%) are Buddhists. The campaign relates drinking abstinence to Buddhism’s concepts of the Five Precepts (the basic code of ethics for lay people), of which abstention from intoxication, including the drinking of alcohol, is one of the precepts. The other precepts include the following:

- to abstain from taking life.

- to abstain from taking what is not given.

- to abstain from sensuous misconduct.

- to abstain from false speech.

The objective of Saengow’s study was to estimate the proportion and number of drinkers changing their drinking behaviours during the Thai 3-month abstinence campaign, and to examine the determinants of alcohol abstinence.

Eligibility criteria for the survey subjects included an age >= 15 years and the ability to communicate in Thai. Almost 70% of the subjects were male and 30% were female.

The total number of survey subjects was 4296, of whom 1486 had drunk in the 12 months prior to the campaign and were considered current drinkers. The estimated drinking prevalence in the Thai population was 34.3%. In the 12 months prior to the campaign, a third of the drinkers drank at least once every week, and a third drank less than once a month. Beer was the most popular alcoholic beverage, followed by spirits and locally made of alcohol. More than 80% of drinkers perceived that alcohol is very harmful. The following table shows the level of participation in the campaign:

| Drinking behaviour | Prevalence (%) | Estimated number of Thai citizens |

| Current drinkers who abstained completely during the 3-month period | 32.2 | 5,772,905 |

| Current drinkers who partially abstained | 16.3 | 2,923,663 |

| Current drinkers who reduced their number of drinks per drinking occasion | 18.7 | 3,345,251 |

| Current drinkers who continued drinking as usual | 32.8 | 5,880,396 |

Table 2: Estimated prevalence and number of drinkers with certain drinking behaviours during the campaign.

The 3-month abstinence campaign in Thailand achieved a higher rate of participation compared to the UK “Dry January” campaign of 1-month duration. The participation rate was 67.2% in Thailand and 11% in the UK 2016. Perhaps this is because Thailand is a relatively dry country; only a third of the population aged 15 and above are current drinkers, while in the UK, the prevalence of current drinkers was 83.9% in 2010. In Thailand, therefore, where drinking is NOT the norm, encouraging people to abstain from drinking might be easier.

The anticipated outcomes of these challenges is a reduction of alcohol consumption after the challenge ends. That doesn’t always happen.

In many studies, participants demonstrated an enduring reductio in alcohol consumption, an increase in drink refusal self-efficacy, and improvements in wellbeing, and mental and physical health.

However, there are some reports which show that these improvements were not maintained following the resumption of drinking. Furthermore, although drinkers not participating in a temporary alcohol abstinence challenge (TAC) did not reduce their drinking over time, TAC participants reported significantly higher alcohol consumption at baseline compared to the control group (Butters, et. al., 2023).

Factors which promote lasting effects

It appears that making the commitment to participate, including registration, mobile phone applications for goal-setting and progress monitoring, and online peer support groups, may be active ingredients that individually or in combination promote long-term behaviour change.

Butters et. al. (2023) further add the following:

- That participants are more likely to remain abstinent throughout a TAC if they commit to doing so by formally registering;

- Participants who read daily support emails were more likely to remain abstinent during Dry January than those who did not

Butters, A.; Kerbergen, I.; Holmes, J.; Field, M. (2023). Temporary abstinence challenges: What do we need to know? Drug and Alcohol Review 42(5):1087-1091. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13625.

Saengow, U. (2019). Drinking abstinence during a 3-month abstinence campaign in Thailand: weighted analysis of a national representative survey. BMC Public Health (2019) 19:1688, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-88051-z.

P.S.: From Alan Jackson, “It’s 5 o’clock somewhere.”

or this, from Huey Lewis & the News, It’s Hip to Be Square: